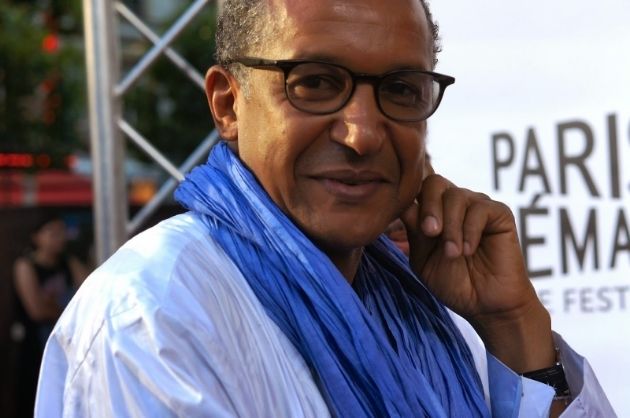

A lot has happened since I talked with Abderramane Sissako last October at the New York Film Festival. Islamic terrorists' attack on the headquarter of French satire magazine Charlie Hebdo and a kosher grocery store in Paris this January shook all of Europe. And Sissako's film Timbuktu got nominated for Best Foreign Film Oscar this year.

The anti-Islam sentiment and jingoism are on the rise in Europe. With that, unfortunately, Timbuktu is embroiled in controversy on the eve of its theatrical release in France. (Read the full article from Washington Post here) It's a pity because Timbuktu is such a beautiful film and a strong condemnation of religious extremism.

The film struck me very strongly. For the little time I was given for the interview, I was fully committed to have Sissako speak about the film the whole duration. But however passionate and knowledgeable he was on the subject, he wasn't interested in schooling me about what happened in Timbuktu, he was more interested in engaging in conversation. For that I am very honored and grateful.

The film opens in New York on January 28 and January 30 in Los Angeles. And in my humble opinion, it should win an Oscar.

TIMBUKTU is such a powerful, tragic film. I know I don't get much time with you so I won't bother with bunch of silly questions. I just want you to talk about the film.

Abderramane Sissako: (laughs) No no no. Of course you can ask questions.

TIMBUKTU is based on/inspired by a true story. I'd like to know how you went about building a film around this true story.

Sometimes you feel that a film is useful and also necessary. I don't know if this is true but it's possible that that is true. It's not that I felt obligated to do so but I felt it was important for me to tell the story and to tell it quickly. Because I think what's happening in this part of the world is not usually told well. Because in the West, we only report about it when it's something that specifically touches us - namely, a hostage. Of course, a hostage is a dramatic situation. But we forget that on a daily bases there are people who are being held hostage and humiliated. When Timbuktu was under siege by Islamic militants, people were having their hands cut off - a guy sees that an air conditioner doesn't work so he goes there to fix it, they think he's stealing it and cut off his hand! It's just horrible. And it's as awful as hostage, but we don't talk about these arms and legs being cut off. So I think what filmmaker needs to do is that he needs to focus on ordinary people and their everyday lives.

People whose daily lives don't appear in the news. To really directly answer your question, this film really took sustenance from the city itself and the beat and the life in it.

One thing that struck me about the film was how diverse the city of Timbuktu is. There are several different languages spoken and different culture presented within the Muslim community. It is a reminiscent of other occupations who bring in their own laws and completely oblivious about the culture and customs of the people who are living there.

Timbuktu is an old city and it's historic. It's always been a meeting place, situated at a crossroads. People from different cultures have always lived there. And that was one of the reasons why they had decided to take Timbuktu, as a symbol. The parallel I can make is in New York after 9/11. What happened in New York, not only people who lived here but everyone felt like a New Yorker because what was happening. Because here every English speaker speaks another language. If you ask anyone on the street they will tell you. And it's this diversity and culture that the city was attacked because it was a symbol and that's why so many people reacted.

You made a film about Poverty of Africa with your last film BAMAKO. It's about the influence of the World Bank and the West and they are literally on trial. This one, even though extreme Islamic fundamentalism stems out of that western influence but you don't talk about the West in this film at all.

I think that's a very good question. With Bamako, I wanted to talk about the fault of other people and I didn't want this film to be like that. In this film, I wanted people to look inward, to look inside themselves and to understand that this is something that that's happening and we could say it's brought on by foreigners but those foreigners are not so distant from who we are. And Timbuktu was liberated by the French army. But I didn't want to show that. What I wanted to show was that the first revolt was by the citizens themselves - people who play soccer without a ball, that's what the resistance is.

Yes.

A woman who sings and they beat her and she sings anyway.

I read about the retreating occupiers burning down the famous Ahmed Baba Institute. I'd like to know if the sense of normalcy came back to Timbuktu after what happened in 2012.

I think the destruction of the library really had a huge impact on many people. The same thing with the mausoleums: the ground burial sites. But what's important to know is that before that happened, a lot of the people in Timbuktu have saved these artifacts. (read about it here) And today the situation is better.

How was your collaboration with your DP, Sofian El Fani (BLUE IS THE WARMEST COLOR), because there are a lot of handheld sequences and a lot of running around?

I knew his work. When I chose him, he also wanted to work with me on the project. So things were very simple between us. He works a lot with (Abdellatif) Kechiche and Kechiche is always about handheld camera and they are very tight shots. What makes El Fani a really great cinematographer is his adaptability. He knew right away what I was looking for in framing.

There were discussions of course. I don't really like closeup shots in cinema. I always want to create space because, for me, that space is an invitation, to enter into it. When I make a film I don say, "look!" I say, "come in".

I know that BAMAKO was funded in part by actor Danny Glover because no one was funding movies of African origin. Was it the case with TIMBUKTU? Was getting funding just as difficult?

No. With Bamako, what Danny Glover did was extraordinary. He was the first person who really believed in the kind of film I wanted to make. And I knew Timbuktu was supposed to be made very quickly, so the funds came very quickly too. So it wasn't really necessary to involve many people.

Oh good.

It was important to move quickly.

How long was the entire shoot?

All together, about six weeks.

Six weeks!? Wow, that's fast.

And these are distances where you are on the road full day. It was very difficult. And of course there were no trails or anything. It's also difficult to deal with people who aren't professional actors for 6 weeks. But you know, sometimes, things are difficult.

But you pulled it off beautifully.

Thank you.

What's next for you?

Without talking too much about it, it's going to be about China and Africa. But a love story.

I will very much look forward to that.

Read my Timbuktu Review Here