Time is a Flat Circle: Temporal Dissonance and Trauma in Christian Petzold’s Dystopian Tale: Transit

I’m thinking about Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return when I think about Christian Petzold’s film Transit. Eternal return/eternal recurrence is a concept that the universe and all existence and energy have been recurring and will continue to recur, in a self-similar form an infinite number of times across infinite time and space. “Time is a flat circle,” is a phrase uttered by Rust Cohle, a character who has a very pessimistic view on human existence in an HBO show True Detective, when he is reminiscing about an old, unsolved case, “Someone once told me time is a flat circle. Everything we’ve ever done, or will do, we are gonna do all over again.” He is suggesting that we are destined to relive the same experience over and over, past and present melding into one another. And this is the case with Transit which takes place in a hypothetical world where fascist Germany is occupying France once again and its characters, traumatized by the unfolding events, enter into a sort of fugue state where there is no escape.

I’m thinking about Nietzsche’s concept of eternal return when I think about Christian Petzold’s film Transit. Eternal return/eternal recurrence is a concept that the universe and all existence and energy have been recurring and will continue to recur, in a self-similar form an infinite number of times across infinite time and space. “Time is a flat circle,” is a phrase uttered by Rust Cohle, a character who has a very pessimistic view on human existence in an HBO show True Detective, when he is reminiscing about an old, unsolved case, “Someone once told me time is a flat circle. Everything we’ve ever done, or will do, we are gonna do all over again.” He is suggesting that we are destined to relive the same experience over and over, past and present melding into one another. And this is the case with Transit which takes place in a hypothetical world where fascist Germany is occupying France once again and its characters, traumatized by the unfolding events, enter into a sort of fugue state where there is no escape.

All characters in Petzold’s films are in a state of uncertainty: they are forced to embark on a journey by the outside forces, rather than by their own volition like in Wim Wenders films or the works of Novalis or Hölderin of German Romanticism. In effect, the title Transit, can be used in all his films, interchangeably, making it a perfect title that emblemizes his work. With Transit, I’d like to examine how temporal, spatial dissonance causes the lasting trauma in people’s psyche and how Petzold and the Berlin School filmmakers use genre conventions to reflect on the post-wall neoliberal Germany as well as its nazi past.

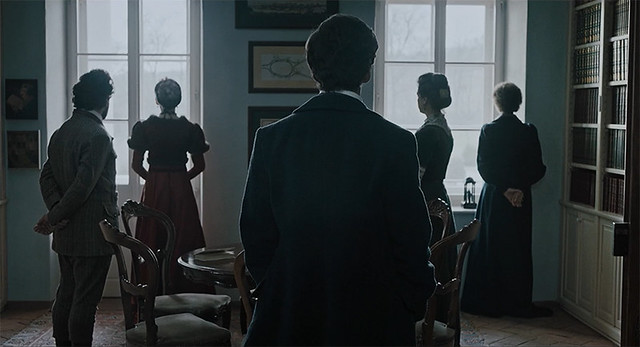

Transit is a novel written by Anna Seghers based on her own experience in France under the nazi occupation in 1942. Petzold transposes its setting to contemporary Europe; a modern day Marseille. The film’s setting can be interpreted as either an alternate reality or a very near future where Germany has become a fascist state yet again. But Petzold goes about presenting this slyly, often blurring the boundaries between past and present - there are no discernable historical/cultural markers in the film- no swastikas, propaganda posters or incendiary slogans on banners in public squares. But the motor-vehicles and police in riot gear suggest that the film takes place in the present day. Pinpointing the film’s timeframe is a tricky business. Judging by the conversation held by characters about a movie about zombies- that even the dead not having much imagination by going to a shopping mall, it alludes to taking place post-1978 or even 2004 (the release year of George Romero’s classic Dawn of the Dead and Zach Snyder’s remake respectively). Curiously, there is no sighting of mobile phones anywhere, adding more confusion to the film’s timeline. There are also no lamentations by any of the characters on how history repeats itself. It’s as if Germany’s dark war past has been deliberately erased from history or invoking its history is a taboo subject. Yet for us audiences, hearing the sound of jackboots marching, a talk of ‘cleansing of the Jews’ and seeing police rounding up people in the streets are familiar sight and sound from countless World War II films set in the cities under nazi Germany. Seeing and hearing this in the present setting is jarring and disorienting. There is a definite temporal dissonance. It’s an interesting choice for Petzold to directly invoke Germany’s nazi past to reflect on the current state of Germany and Europe.

Transit is a novel written by Anna Seghers based on her own experience in France under the nazi occupation in 1942. Petzold transposes its setting to contemporary Europe; a modern day Marseille. The film’s setting can be interpreted as either an alternate reality or a very near future where Germany has become a fascist state yet again. But Petzold goes about presenting this slyly, often blurring the boundaries between past and present - there are no discernable historical/cultural markers in the film- no swastikas, propaganda posters or incendiary slogans on banners in public squares. But the motor-vehicles and police in riot gear suggest that the film takes place in the present day. Pinpointing the film’s timeframe is a tricky business. Judging by the conversation held by characters about a movie about zombies- that even the dead not having much imagination by going to a shopping mall, it alludes to taking place post-1978 or even 2004 (the release year of George Romero’s classic Dawn of the Dead and Zach Snyder’s remake respectively). Curiously, there is no sighting of mobile phones anywhere, adding more confusion to the film’s timeline. There are also no lamentations by any of the characters on how history repeats itself. It’s as if Germany’s dark war past has been deliberately erased from history or invoking its history is a taboo subject. Yet for us audiences, hearing the sound of jackboots marching, a talk of ‘cleansing of the Jews’ and seeing police rounding up people in the streets are familiar sight and sound from countless World War II films set in the cities under nazi Germany. Seeing and hearing this in the present setting is jarring and disorienting. There is a definite temporal dissonance. It’s an interesting choice for Petzold to directly invoke Germany’s nazi past to reflect on the current state of Germany and Europe.

Transit was released in 2018 under the shadow of the foiled assassination plot on the German Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2016 and after the extreme right-wing nationalist party AfD (Alternative für Deutschland) gained 12.6 percent of the seats in the German Parliament in 2017 (later it became the largest opposition party). Germany’s white nationalist movement has seen a steady growth since the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989. With the influx of over 1.2 million immigrants (not counting 3 million Turkish descent German citizens who have been living there since the 60s), the racial violence against ‘outsiders’- meaning, against people of the Middle-Eastern and African origin as well as German Jews, has been increasing over the recent years. According to the Interior Ministry data, xenophobic acts of violence saw 19.7 percent jump in 2017 from the previous year.

Christian Petzold, as a leading figure in the Berlin School which is Germany’s most significant film movement since the New German cinema of the 60s and 70s and a prominent voice in a recent surge of German cinema in the global stage, has been making films that reflect the cultural & political landscape and collective German psyche in the post-wall, neo-liberal era Germany. The Berlin School is a term given to a group of loosely connected filmmakers who attended German Film and Television Academy (DFFB) in the late 80s and early 90s, namely Thomas Arslan, Christian Petzold and Angela Schanelec - known as ‘The First Wave’. Ulrich Köhler, Valeska Grisebach, Christoph Hochhäusler, Maren Ade and many more were considered and later added to the growing list of like-minded filmmakers. The main themes these filmmakers share in their work are: loss of identity, guilt, aimlessness and dislocation under neo-liberal Germany. One of the main themes they often deal with is, as Marco Abel puts it, ‘sehnsucht’ (longing): a longing for Germany that has never materialized under neoliberal capitalism. The Berlin School, in effect, is about ‘reseeing’ Germany.

Utilizing genre conventions and twisting them to reflect on the current state of the post-wall Germany is a tendency of many filmmakers of the Berlin School: Heist films/thrillers/noir are bread and butter for many - The City Below, The Lies of the Victors (Christoph Hochhäusler), In the Shadows (Thomas Arslan), The Robber (Benjamin Heisenberg), The Dreileben Trilogy (Höchhausler, Dominic Graf and Petzold). They also dabbled in Western - Gold (Arslan), horror - Yella (Petzold), Sci-fi - In My Room (Ulrich Köhler) and fantasy - Undine (Petzold), just to name a few.

Although many critics emphasized the Berlin School’s presentist and realist approach – the contemporary world observed in almost obsessive detail, Petzold has been deeply concerned with history in various ways throughout his filmography. Especially with his last four output - Barbara (2012) a period film that takes place in East Germany in the 80s, Phoenix (2014), set in the aftermath of WWII, Transit (2018), set in the near future/alternate present where Europe is in the grips of Fascist German regime once again and Undine (2020), his take on folklore/fantasy genre, investigating Berlin’s tumultuous past just underneath the surface of fast changing city, Petzold, unlike most of his compatriots of the Berlin School, does not shy away from Germany’s ugly war past and have found innovative approaches to address the same inquiry through genre conventions the unfulfilled desire of finding a collective utopia that is ‘Deutschland’.

Gilles Deleuze talks about ‘time out of joint’ in Cinema 2: The Time-Image. It was the Second World War that changed cinema from movement-image to time-image based medium. It signifies that time is no longer subordinated to movement, but rather movement to time. This break happened because of the devastation the war brought: atrocities in situations we no longer knew how to react to, rubbles in spaces we no longer knew how to describe. In these leveled cityscapes, a new race of characters was born: they saw rather than acted- they were seers.

Transit starts with Georg (Franz Rogowski) being asked to deliver two letters to Weidel, a writer of some importance in Paris by an acquaintance at the bar. It's a dangerous mission- there are police raids daily and it's harder to get around on the street without constantly being asked for proper papers. Everyone knows a major crackdown is about to happen: already there are people being dragged away in the streets by the heavily armed authorities- 'the purge/cleansing' is just around the corner. But with some money promised, Georg is game. Georg is a typical (anti)hero of the Berlin School films - unmotivated, lost, just going through the motions, like a ghost among his fellow citizens. He is an observer, not a participant. He scoffs at the notion of “danger visa,” when the acquaintance tells him why he can’t make the delivery himself since he is deemed ‘dangerous’. Georg is nobody special. Just a face in the crowd. Petzold makes sure that he is not the narrator of his own story by inserting a voice over of a man, completely unrelated to the main characters, who turns out to be a bartender in Marseille later on. Once Georg gets to Paris, he finds out that the writer has committed suicide, leaving his documents and the latest manuscript behind. With some more money promised, he reluctantly takes a sick man wanted by authority along with him on a train (as stowaways) to Marseilles. Once he gets there, he is to notify the Mexican consulate about the death of the writer. Weidel’s documents reveal that he had a safe passage arranged for him and his wife Marie (Paula Beer) to go to Mexico. The letter Georg was supposed to deliver to Weidel is from Marie, declaring that she is leaving him.

Once he arrives in Marseilles, Georg assumes the identity of Weidel as he is mistaken for the dead writer at the Mexican Consulate. He makes friends with an Arab immigrant boy whose dad (the sick man) died on the way. He also sees Marie everywhere, scouring the city for Weidel, her husband, day in and day out. Her search is intensified since Georg assumed her dead husband’s identity. So she thinks he is still alive, but avoiding her. This is where Transit embraces a full noir/thriller genre. Petzold’s penchant for genre cinema is pretty well known, as his films often borrow major aspects of their plots from the “cemetery of genre cinema, from the remainders that are still there for the taking.” For example, Jerichow is his adaptation of Jame M. Cain’s pulp noir Postman Always Rings Twice, with the victim switched to a successful small-time Turkish businessman. With Yella, the director takes direct cues from an American b-horror movie Carnival of Souls. In Something to Remind Me and Phoenix, the plots play out like an inverted Vertigo with the loss of identity/false identity playing a big role (also in Transit). His love for the noir/thriller genre is well known; his recent praise of generic American heist thrillers such as Den of Thieves confirms this fact. They are also present in his TV work (Polizeiruf 110), as well as most of his films.

Transit’s alternate reality fits the description of Deleuze’s modern cinema very well. “As for the distinction between subjective and objective, it also tends to lose its importance, to the extent that the optical situation or visual description replaces the motor action. We run in fact into a principle of indeterminability, of indiscernibility: we no longer know what is imaginary or real, physical or mental, in the situation, not because they are confused, but because we do not have to know and there is no longer even a place from which to ask. It is as if the real and the imaginary were running after each other, as if each was being reflected in the other, around a point of indiscernibility.” Marseille is ‘any-space-whatever’ Deleuze talks about in Cinema II as well. In Transit Marseille is not quite the rubble or empty factories that lay waste in the aftermath of WWII. But it’s not the bustling second largest French city with shops and beaches either. In the film, it is a sparsely populated, lifeless place where lost people in transit converge, waiting to set sail for their new destinies. It is a mere place to pass through. Waiting however, is exactly what these people do which seems eternal. Marie is involved with Richard (Godehard Giese), a doctor who has put his departure on hold because he doesn't want to leave her behind. No one wants to be the one who leaves. These characters are stuck in there, trapped by love, by the sense of loyalty, by guilt. Transit's got a lot to do with guilty conscience: guilt of leaving someone behind. Guilt of forgetting. Guilt of being indifferent. Time seems to stand still in Marseille, as characters run around in circles, day after day, waiting for what they desire that will never materialize, while the ‘cleansing’ is inching closer to them (the rumour has it, the cleansing is happening in nearby Avignon).

Transit’s alternate reality fits the description of Deleuze’s modern cinema very well. “As for the distinction between subjective and objective, it also tends to lose its importance, to the extent that the optical situation or visual description replaces the motor action. We run in fact into a principle of indeterminability, of indiscernibility: we no longer know what is imaginary or real, physical or mental, in the situation, not because they are confused, but because we do not have to know and there is no longer even a place from which to ask. It is as if the real and the imaginary were running after each other, as if each was being reflected in the other, around a point of indiscernibility.” Marseille is ‘any-space-whatever’ Deleuze talks about in Cinema II as well. In Transit Marseille is not quite the rubble or empty factories that lay waste in the aftermath of WWII. But it’s not the bustling second largest French city with shops and beaches either. In the film, it is a sparsely populated, lifeless place where lost people in transit converge, waiting to set sail for their new destinies. It is a mere place to pass through. Waiting however, is exactly what these people do which seems eternal. Marie is involved with Richard (Godehard Giese), a doctor who has put his departure on hold because he doesn't want to leave her behind. No one wants to be the one who leaves. These characters are stuck in there, trapped by love, by the sense of loyalty, by guilt. Transit's got a lot to do with guilty conscience: guilt of leaving someone behind. Guilt of forgetting. Guilt of being indifferent. Time seems to stand still in Marseille, as characters run around in circles, day after day, waiting for what they desire that will never materialize, while the ‘cleansing’ is inching closer to them (the rumour has it, the cleansing is happening in nearby Avignon).

‘Wartender/Waiting’ happens to be the title of Weidel’s last manuscript that Georg carried from Paris to Marseille. It turns out to be a good reflection of what Georg and Marie are experiencing. Out of boredom in transit to Marseille, Georg reads the manuscript and has an opportunity to tell its story to an arrogant consul at the American embassy when asked about his/Weidel’s new book. In this ‘story within a story’, the main character is dead and waiting to register in hell at the gate. The waiting turns from hours to days to weeks to months to years. After many years have passed, the character asks the gatekeeper just when he will be admitted to hell. The gatekeeper tells him, “Why man, this IS hell!”

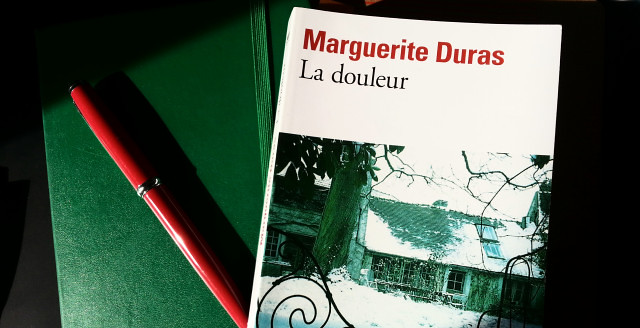

Experiencing any war is painful. Its effect lingers for a long time - maybe for decades, over generations. The American Psychological Association defines trauma as the lingering psychological and emotional response to a singular traumatic event that threatens injury, death, or the physical integrity of self or others and also causes horror, terror, or helplessness at the time it occurs. The French literary giant Marguerite Duras, in an introduction to her memoir with a very literal title- La Douleur/The Pain, culled from her essays and diaries in the occupied France during WWII, as she was involved in the resistance movement and waiting for her husband’s return from a concentration camp, she claims that she doesn’t remember writing those words, "When would I have done so, in what year, at what times of day, in what house? I can't remember." The emptiness left by the absence of her loved one is so great, she would lose herself.

If there were another title that can encapsulate the theme of all of Petzold’s films other than Transit, it would be ‘ghost’. Some critics grouped three of his earlier films ‘The Ghost Trilogy - The State I am In (2000), Ghosts (2005) and Yella (2007) for portraying characters who have to contend, one way or another, with the economic hardships and invisibility in post-wall neoliberal Germany. But his subsequent works, along with the theme of transient lives, Petzold’s protagonists suffer from loss of identity and invisibility also. Burdened with terrible secrets they can’t reveal, they tread their paths as if on eggshells - like the East German doctor who hides her intentions to defect to the West in Barbara, a disfigured concentration camp survivor who has to go along with her new identity in Phoenix, Georg who assumes the dead man’s identity but can’t reveal his secret in Transit. It might be a different pain: one caused by economic hardship in highly capitalistic society, the other caused by violence of war. But they both make ghosts out of people who experience them. The economic disparities and characters with lost identities in Petzold’s earlier films and many other works by the Berlin School filmmakers can be attributed all the way back to atrocities of the nazi Germany in WWII. Losing oneself, losing one’s identity is deeply entwined with the survivors’ guilt, the guilt of leaving others behind/betraying others. That guilt for those who remember the past, never really went away. They have been the theme of Duras and many of the Nouveau Roman writers as well as all Petzold’s films and many of other directors in the Berlin School.

Let’s put the film in context of the world events in 2017-18; the Syrian civil war was still raging and the refugee crisis was deepening, Trump enacted the Muslim Ban restricting visas from 7 predominently muslim countries, started to build the wall in the southern border with Mexico, the Israel-Palestine conflict intensified, just to name a few. It is not difficult to see what is reflected in Transit is not far from what’s been happening on the news on TV every night. The future is already here: the film’s premise, the ugly past repeating itself and its temporal dissonance says a lot about the highly advanced capitalist, neoliberal society. The world is moving too fast, while humanity has a little time to reflect on the past. I see Transit as an allegory of Germany’s war past and its citizen’s collective, willful amnesia, caused by the war itself. Hence, the merry-go-round of war - trauma - collective amnesia - war - trauma - collective amnesia being repeated. Suffering from an identity crisis, Georg desperately tries to save Marie while concealing the bitter truth that Weidel is dead and gone all in the midst of fascist takeover: Georg is a stand-in for Germany, Weidel for the utopia that never materialised and Marie for the country’s future/younger generation. Going back to Sehnsucht/longing for the utopian Germany that never was, and regarding Germany’s dark history repeating in Transit, I believe Petzold is telling us that however painful it is, we will have to face the past in order to understand trauma so we don’t repeat it.

Let’s put the film in context of the world events in 2017-18; the Syrian civil war was still raging and the refugee crisis was deepening, Trump enacted the Muslim Ban restricting visas from 7 predominently muslim countries, started to build the wall in the southern border with Mexico, the Israel-Palestine conflict intensified, just to name a few. It is not difficult to see what is reflected in Transit is not far from what’s been happening on the news on TV every night. The future is already here: the film’s premise, the ugly past repeating itself and its temporal dissonance says a lot about the highly advanced capitalist, neoliberal society. The world is moving too fast, while humanity has a little time to reflect on the past. I see Transit as an allegory of Germany’s war past and its citizen’s collective, willful amnesia, caused by the war itself. Hence, the merry-go-round of war - trauma - collective amnesia - war - trauma - collective amnesia being repeated. Suffering from an identity crisis, Georg desperately tries to save Marie while concealing the bitter truth that Weidel is dead and gone all in the midst of fascist takeover: Georg is a stand-in for Germany, Weidel for the utopia that never materialised and Marie for the country’s future/younger generation. Going back to Sehnsucht/longing for the utopian Germany that never was, and regarding Germany’s dark history repeating in Transit, I believe Petzold is telling us that however painful it is, we will have to face the past in order to understand trauma so we don’t repeat it.

Sources Consulted

1. Abel, Marco. The Counter-Cinema of the Berlin School. Boydell and Brewer, 2013: 1-28, 69-110

2. Chang, Dustin. “I Envision All These Great Small Movies in the Ruins of Hollywood: Chrsitan Petzold Interview, Screen Anarchy, December 12, 2012

https://screenanarchy.com/2012/12/i-envision-all-these-great-small-movies-in-the-ruins-o

f-hollywood-christian-petzold-interview.html

3. Deleuze, Gilles. Cinema 2: The Time-Image, University of Minnesota Press, 1989: xi, 1-67

4. Hamann, Hilary Thayer. “A Harsh Tale of War, But Unforgettable Read,” NPR, February 16, 2011

https://www.npr.org/2011/06/29/133811002/a-harsh-tale-of-war-but-an-unforgettable-read

5. Mirthy, Vikram. “Christian Petzold on Transit, Kafka, His Love for Den of Thieves and More,” RogerEbert.com, February 24, 2019

https://www.rogerebert.com/interviews/christian-petzold-on-transit-kafka-his-love-for-den-of-thieves-and-more

6. Mudd, Cass. “What the stunning success of AfD means for Germany and Europe,” The Guardian, September 27. 2017

https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2017/sep/24/germany-elections-afd-europe-immigration-merkel-radical-right

7. Staff. “Germany sees extremely alarming rise in racist and anti-semitic hate crime,” The Local, May 14, 2019

https://www.thelocal.de/20190514/germany-sees-extremely-alarming-rise-in-racist-and-anti-semitic-hate-crime

In a coastal fishing village in Gallicia is experiencing another ocean related tragedy; Rubio, a fisherman who is known for retrieving dead bodies of shipwreck victims so the mourning villagers can have closures, became the victim himself of the tumultuous waves off the coast when his ship sank. His body might never be found. The local legend dictates that there is a monster living in the dark sea, awakened by the devil moon. Three ancient witches come in to town, to take its villagers who seem to be immobilized by grief on the spot where they stand by shrouding them over with white clothes making them a literal ghosts statues, while under red moon. And that's the gist of the story in Lúa Vermella.

In a coastal fishing village in Gallicia is experiencing another ocean related tragedy; Rubio, a fisherman who is known for retrieving dead bodies of shipwreck victims so the mourning villagers can have closures, became the victim himself of the tumultuous waves off the coast when his ship sank. His body might never be found. The local legend dictates that there is a monster living in the dark sea, awakened by the devil moon. Three ancient witches come in to town, to take its villagers who seem to be immobilized by grief on the spot where they stand by shrouding them over with white clothes making them a literal ghosts statues, while under red moon. And that's the gist of the story in Lúa Vermella.