With theatrical release of the digitally restored 1997 film LEVEL 5, Brooklyn's own BAM Cinematek is hosting a rare retrospective of Chris Marker, one of the most singular voices in cinema history.

Marker passed on in 2012. But as a writer, photographer, visual essayist and multimedia artist, Marker leaves impressive body of work that spans more than a half a century. His uncategorizable cinematic oeuvre touched upon politics, technology, cinema, artists, time and memories. He was an acute observer of the past and present and cinema's own soothsayer.

The retro includes Sunless: one of my absolute favorites, La Jetée: a seminal time-travel Sci-fi classic, Bestiary Series: his short visual haikus on animals, Statues Also Die (with Alain Resnais) and Valparaiso (with Joris Ivens): his collaborative efforts, The Six Side of the Pentagon, Le Joli Mai and other politically themed time capsules, One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenivich, Remembrance of Things to Come: biographical sketches, and a lot more.

Chris Marker Retrospective runs 8/15 - 8/28. For tickets and more information, please visit BAM Cinematek website.

Level Five (1997)

The act of remembering has always been Chris Marker's theme. Using the then relatively-new technology called internet, the famed visual essayist equates information/misinformation with distorted history in the sci-fi mold. Yes, DOS era graphics are laughably outdated, but Marker's prediction is alarmingly accurate: masks (avatars), OWL, short for optional world link (a stand in for world wide web), skyping, internet anonymity, personal connection/disconnection....

Laura (Catherine Belkhodja), named after Otto Preminger's heroine by her internet correspondent, inherits the research on the largely forgotten Battle of Okinawa for creating a computer game. So day in and day out, in her pajamas, Laura sits at her computer table researching that fateful battle in a windowless, dark room, looking and addressing directly to the camera.

Marker also inserts interviews with Oshima Nagisa , author/scholar Tokitsu Kenji, the survivors and war/tour footage of Okinawa. As Oshima says in the interview, Okinawa was sacrificed in the hopes of saving the mainland. The battle was already a foregone conclusion. The civilians were ordered to kill themselves ahead of the battle, to avoid being captured by evil enemies. As a result 130,000 civilians died on that island. They killed their loved ones and killed themselves. Japanese commanders were banking on the resolve of civilians deterring the enemies. Instead, atom bombs were dropped on the mainland two months later.

Marker's contemplation on people imbued with the new technology (William Gibson style) and the history falling into oblivion is not always successful. But it is a potent film with a long lasting implication on the matter.

Digitally restored, Level Five has a week-long theatrical release August 15-21, running concurrently with the retrospective.

Statues Also Die (1953)

In this short docu-essay commissioned by Présence Africane journal, the filmmakers examine African art and its commercialization by way of colonialism. Marker, who handled the camera, shoots African statues and masks like they are human beings, not museum pieces on a mantel, since they are not represented in museums like Louvre.

Resnais and Marker make a case that a statue loses its meaning when it ends up on text books or taken completely out of context (mass produced or becomes an ashtray). That's how they die. Their utilitarian and cultural applications aside, African art doesn't get no respect as art.

I don't know if the footage of the Harlem Globetrotters is meant to be cynical or genuine adoration of athletic prowess, but the filmmakers cover the ugly side-effects of colonialism -- Disney-fying Africa. It is remarkable considering it was made in 1953, way before many African nations' independence from its European colonizers or American Civil Rights movement. No wonder it was banned from the French public until 1963.

In its entirety:

Sunless (1983)

Sublime. Marker's musings on impermanence of human existence and memories narrated by a female narrator are both poetic and thoughtful. The 80's Japan takes the center stage as an alien world where a thousand years of time criss-crossing in every street corner, Kilgore Trout style.

While Godard tries to cram a lot of the same ideas in his films but never manages successfully to fully articulate them, Marker does it so effortlessly here. Beautiful and wise beyond anything I've seen or read.

The Koumiko Mystery (1967)

It's Koumiko, a twenty-something Japanese beauty who fast derails Marker's coverage of the 1964 Tokyo Olympics. He can't take the camera away from her angular, very traditional Japanese face. The film consists of some narration by the filmmaker, newscasters and Koumiko herself as she answers Marker's barrage of questions honestly with that typical Japanese modesty, but always with a hint of mystery.

The film is an anthropological travelogue, documenting post-war Japanese psyche in the shadow of the greatest economic miracle the world has ever seen. Koumiko, an apolitical woman whose ancient face betrays modern sensibilities as she talks about her life and men is at once traditional and contemporary.

As the title suggests, Marker knows the seductive power of something hidden. You can't possibly find out about someone in 46 minutes, let alone a whole country. He knows this. But the film is a lyrical, beautiful ode to that first glimpse, peeling off that first layer. Beautifully shot and edited, I long to see this film on the big screen.

Koumiko marks the beginning of Marker's fascination with Japan, the setting of many of his later films. It also introduces cats, a constantly recurring motif in his work.

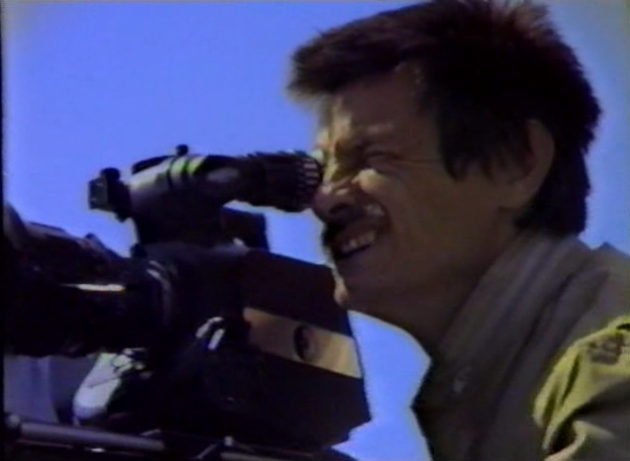

One Day in the Life of Andrei Arsenevich (2001)

Made for French TV, Cinema de notre temps, Marker faithfully records the last days of the Russian master, Andrei Tarkovsky, who died in a Paris hospital in 1986, soon after completing his last film, The Sacrifice. With footage from Tarkovsky's other films, Marker assembles an intimate and revealing documentary about the Russian master's philosophy, techniques and intersection of his life and art.

One Day in the Life... is a top rate analysis of Tarkovsky's mastery and contains many precious glimpses of the master at work, especially in filming bravura ending of Sacrifice where continuous long shot of burning house and Alexander (played by Ingmar Bergman regular Erland Josephson) running left and right. On camera, captured by Marker, unlike the solemnity of the scene, Tarkovsky is joyful and energetic, dictating every inch of action and camera movement to actors and Sven Nykvist (master DP, also a Bergman cohort). This is a great doc on one of the greatest filmmakers ever lived.