Political, Cultural Resistance: The Spirit of Third Cinema Continues to Live on in Contemporary Brazilian Cinema: Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles’ Bacurau and Gabriel Mascaro’s DivineLove/Divino Amor

Let's consider what's been happening in Brazil recently. In early 2018, Luiz Ignacio Lula de Silva, affectionately known as Lula, a much loved labor leader and former two-term Brazilian president, was barred to run for president again because of the trumped up corruption charges and sentenced to 12 years in prison, in all likelihood by opposing conservative Social Liberal Party, led by Jair Bolsonaro, a foul mouthed, all out bigoted racist who ran on his presidential campaign of fearmongering. It was widely expected that Lula was going to win. But with him being jailed, his Worker's Party's nominee Fernando Haddard ended up losing in the runoff. So now Brazil has the socially conservative and known racist Bolsonaro for president. His U.S.-friendly, pro-corporate, pro-logging, anti-regulation agenda with contempt for indigenous population has created perhaps the most serious eco-disaster in the Amazon rainforest in decades. The most devastating forest fire erupted in 2019, as the rest of the world helplessly watched it burn on the sidelines. Its oxygen rich ecosystem and natives’ habitats were irrevocably damaged.

Brazilian film scene was having its renaissance in the last two decades under the Lula's Worker's Party leadership. The money was flowing into the arts and to the once neglected regions of Brazil. Pernambuco, a northeastern state with its multicultural capital Recifé has emerged as an economical, cultural center, producing many emerging local film directors like Kleber Mendonça Filho, Adirley Queirós and Gabriel Mascaro, taking the limelight away from the rich Southern part of the country - Rio, Bahia and Sao Paolo. Bolsonaro's austerity measures are undoubtedly putting a hard brake on this growing Brazilian film movement which is perhaps the most significant since the days of Cinema Novo, and the full impact is still yet to be seen.

Third Cinema, the term coined by two Argentines, Fernando Solanas and Octavio Getino in their influential manifesto :Toward a Third Cinema (1969), decries neoliberalism, the capitalist system, and the Hollywood model of cinema as mere entertainment to make money. This is largely to do with the fact that both Marxism and Third Cinema are preoccupied with inequalities resulting from capital accumulation, of which colonialism is the most extreme manifestation. Aesthetically, the movement drew on Soviet montage, surrealism, Italian neorealism, Brechtian epic theater, cinema verité and the French New Wave. Cinema Novo in Brazil, along with other Latin American countries’ revolutionary filmmaking, was a big part of Third Cinema. Championed by Glauber Rocha among others, Cinema Novo saw an inseparable connection between political struggle and cultural production. Cinema Novo flourished under popular Democratic President João Goulart until he was removed by the U.S. backed military coup in 1964. But it continued to produce films until the mid-1970s. It was Rocha’s 1969 manifesto The Aesthetics of Hunger which directly lays out the principles for Cinema Novo.

This economic and political conditioning has led us to philosophical undernourishment and to impotence - sometimes conscious, other times not. The first engenders simply an alarming symptom; it is the essence of our society. Herein lies the tragic originality of Cinema Novo in relation to world cinema. Our originality is our hunger and our greatest misery is that this hunger is felt but not intellectually understood…. We know- since we made those ugly, sad films, those screaming, desperate films in which reason has not always prevailed- that this hunger will not be assuaged by moderate government reforms and that the cloak of technicolor cannot hide, but rather only aggravates, its tumours. Therefore only a culture of hunger can qualitatively surpass its own structures by undermining and destroying them.

Rocha goes on to defend violence depicted in films of Cinema Novo as a noble cultural manifestation of hunger. It’s at the violence the colonizer suddenly becomes aware of the existence of the colonized. Some of the notable Cinema Novo films are Rocha’s Black God, White Devil/Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964), Antonio das Mortes (1969) and Nelson Pereira dos Santos’s How Tasty was My Little Frenchman/Como Era Gostoso o Meu Francês (1971). Rocha’s films drew from Western genre (both Hollywood and spaghetti Westerns), taking places in sertão (backcountry- the vast arid region in the Northeast Brazil), with cangaceiros (bandits) and land owners. Steeped in mysticism and political allegory, these films tell stories about class struggles and redemption. In How Tasty Was My Little Frenchman, Pereira dos Santos uses ethnological documentary aesthetics into a period piece that is a biting political/cultural satire which takes The Aesthetics of Hunger quite literally.

This paper will be an exploration of Third Cinema and its influence and continuation through two recent Brazilian films Bacurau and Divino Amor by directors Kleber Mendonça Filho & Juliano Dornelles and Gabriel Mascaro. The directors hail from Pernambuco, the formerly neglected northeast region of Brazil and its capital Recifé. Along with fellow Northeasterner Adirley Queirós (from inland Morro Agudo de Goiás, near the country’s capital Brasilia), they have been making politically charged, genre bending films, countering long dominance of more wealthy southern states’ commercialized film industry and ratcheting up their antics after the extreme right wing politician Bolsonaro was sworn in as the country’s president in 2018. I will discuss current Brazilian cinema’s defiance against political tyranny, carrying on if not the aesthetics, but the spirits, of Third Cinema in two chapters. Chapter one will concentrate on anger: Mendonça Filho’s Bacurau. In this violent revenge fantasy, borrowing heavily from genre cinema and tapping into the anger of Third Cinema as expressed by Rocha, the film actively challenges the First World hegemony and recent political climate, critiquing impending ecological peril the country is now facing in the age of globalization. Chapter two will focus on the conservative regime’s cultural crusade against what they see as decades of ‘moral decline’ under the communist-socialist ideological wing of the country. Mascaro’s Divino Amor, a dystopian tale set in the near future is a barely disguised critique on Bolsonaro’s agenda against minorities and the poor in one of the most culturally, ethnically diverse countries in the world.

Chapter 1: Anger

Filmmaker Kleber Mendonça Filho’s two previous feature films Neighboring Sounds/O Som ao Redor in 2012 and Aquarius in 2016, both shot in his hometown of Recifé, were rather subtle, yet pointed critique on rapidly gentrifying neighborhoods in a country where people saw growing middle class in a relative economic prosperity under the democratic government after decades of military dictatorship. Both films deal with gentrification and underlying tensions between different classes while giving historical contexts of the region - often written in blood with cattle ranchers and bandits. These tensions, not explicitly stated, were shown in spurts; in Neighboring Sounds, which is from the perspective of a young upper-middle class gentrifier, there is a bath scene where the waterfall turns into blood. In Aquarius, a middle class family matriarch who stands alone against a development company to defend her apartment that she spent her whole life in from being demolished. But she can’t hide her ignorance at her long time housekeeper’s living conditions; while walking on the beach with her old friends, she points to the invisible line in the sands, “Over this line is the part of the town where poor folks live,” and her housekeeper replies, “Yes, Clara. That’s where I live.” Both Neighboring Sounds and Aquarius are far from “ugly, sad films, those screaming, desperate films” described in The Aesthetics of Hunger by Rocha. They are well made films with professional crew and actors and high production value. But they certainly have scathing moments of social commentaries. Still, they don’t prepare you for the tremendous anger felt in Bacurau. co-written and co-directed by Mendonça Filho and his long time production designer Juliano Dornelles, Bacurau is a Sci-fi Western that takes place in sertão in the near future. It’s also a revenge film with almost cartoonish violence inflicted upon its mercenary First World (mostly American) invaders. As Rocha and other filmmakers decried centuries old colonialism by the imperialist First World countries (first by Portugal, then by U.S. in the form of military coup) and its repercussions 50 years later, we get to witness a new kind of colonialism taking place in the globalization era in the form of foreign financial conglomerates. According to Amazon Watch, a non-profit watchdog group, the devastating fires is the direct result of deforestation brought on by cattle ranching and soy farming, with beef and soy being the two major exports of Brazil. With deregulation and pro-foreign investment favored by Bolsonaro’s regime, big US agribusiness companies like Archer Daniels Midland (ADM) and Cargill, investment firms and banks- BlackRock, T. Rowe Price, Chase, City Bank, Bank of America are major beneficiaries in these transactions. In the Bolsonaro era Brazil, it is quite clear that the country is experiencing neo-colonialism.

In Bacurau, Brazil in the near future is in a state of emergency and government troops are everywhere with road blocks and limiting people’s mobility. Bacurau is a dusty town too small even to be on the map in the Northeast region of Brazil. It is inhabited by a fiercely independent, self-sustaining, proud people largely cut off from the outside world. The glimpse of satellite TV and radio tell grim stories of lawlessness in urban areas. Teresa (Barbara Colen) is returning to attend the funeral of the town's matriarch. Evading the law and roadblocks guarded by heavily armed government troops, she is bringing medical supplies and water to the residents of the town. There's a shortage of everything - food, water, medicine, household items, tampons, etc. Everything is brought in from the outside world and distributed among the townsfolk for their needs. Bacurauans seems to be a well organized social collective, living relatively well despite the rest of the world seems to be falling apart. The town, like any other small town, people know one another and there are some frictions among them. But generally they get along. Then we see a sign of trouble brewing. First, a farmer spots a UFO shaped drone in the sky. And two city folks in fancy motorbikes in neon colored spandex show up in town, confusing everyone. Their cockiness and otherworldliness is duly noted by its residents. They turn out to be a sort of a local guide for heavily armed mostly American mercenaries, led by Michael (Udo Kier). They are there to literally wipe Bacurau off the map. Most of these gungho people-hunters are ex-military officers trying to blow off some steam by going to (any) ‘Third World’ countries and killing its inhabitants with the support of the local government. After a few horrible massacres in the outskirts of the city, Bacurauans realize what's happening to them. But what the hunting party doesn't realize is that these Brazilian country hicks are weather worn, experienced and deeply proud people who are not going to go down easily. One by one, the hunters become the hunted. By using Udo Kier, the blonde haired, blue eyed icon of European and American cult cinema (The Story of O, Blood for Dracula), as the leader of the deranged human hunting game expedition and Sonia Braga (Lady on the Bus, Kiss of the Spider Woman) the beloved legendary Brazilian actress (who also stars in Aquarius), as a matriarchal leader of Bacurau, the filmmakers are making an unsubtle point here; it’s us Brazilians versus Europeans and gungho gringos. The violence that Bacurauans inflict on the hunting party way over the top, especially when it’s performed by Lunga, a charismatic leader of the modern day cangaceiros, played by a famous transvestite stage personality and queer activist, Silvero Pereira. It is a bold choice to use Silveira in such a role since Bolsonaro and Pereira have been engaging in verbal jabs in public. As the Bacurauans get rid of foreigners and local traitors, at a glance, without the context of what's happening in Brazil, the film is a silly, tacky man-hunting-man akin to The Most Dangerous Game or Naked Prey. But it isn't. Bacurau highlights the resilience and resolve of Brazilian people against mounting assault of multinational corporations backed by the Government military in a neo-colonial global economy.

Chapter 2: Christianity as a Form of Colonialism

Rocha warns in The Aesthetics of Hunger that “what distinguishes yesterday’s colonialism from today’s is merely the more refined forms employed by the contemporary coloniser.” and “Thus, our possible liberation is always a function of a new dependency.” In his first film, Black God, White Devil/Deus e o Diabo na Terra do Sol (1964), he calls for denouncing all political and religious doctrine in favor of individual liberty at one with nature.

2010 census reveals that sixty five percent of Brazilians consider themselves Catholic (down from ninety percent a few decades ago), followed by twenty two percent Evangelical Protestant with numbers of agnostics growing rapidly. Since the Portuguese colonial times, confluence of religions of African slaves and natives, Brazil has always maintained a diverse array of syncretistic practices under the overarching umbrella of Brazilian Catholicism. But it’s that tropical multiculturalism with diverse race, culture and gender is what Brazil has been always known for. While Catholics are evenly split between the right and the left in their political spectrum, Evangelicals are mostly conservative and over the years have become an increasingly influential presence in Brazilian politics. And Bolsonaro’s religious themed presidential campaign spoke to them. His retrograde message was a reaction to the advances they have seen since the 1960s in discussions about the family, the place of women, youth and sexuality. It was a Christian morality that tries to recover an idealized past that never existed. Bolsonaro brilliantly tied the message of ‘political corruption’ with ‘moral decay’, and the voters, suffering from recent recession in need to be dependent upon something, found solace in Bolsonaro’s conservative message.

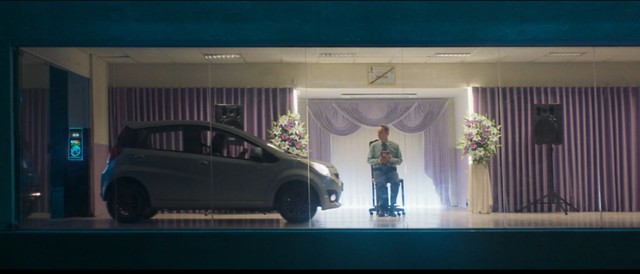

Gabriel Mascaro, filmmaker and visual artist, of such sensual films as August Winds/Ventos de Agosto (2014) and Neon Bull/Boi Neon (2015), have been subverting the stereotypes in gender roles. His films are filled with strong women and men with domestically inclined tendencies. With his new film Divine Love/Divino Amor (2019), Mascaro is charting a new territory, using Sci-fi genre (like Mendonça Filho and also Adirley Queirós with their films) to reflect on the current political climate. It's 2027 Brazil. The country has gone full Christian fundamentalist. Mascaro's version of it is all neon and electronic music. Joana (Dira Paes) and Danilo (Julio Machado) are a middle class couple. She is a notary public, working in a gigantic concrete government building and he is a florist, working in their ground floor apartment complex. They haven't been able to conceive a child even though they try every possible way, method and modern medicine. Something is wrong with Danilo's sperm. They belong to Divine Love, a Christian religious group exclusively for couples. It's a cult like therapy/support group for couples who've had marriage troubles before. They do trust-exercises and even share partners in bed. Joana, using her position of power as a bureaucrat, has been discouraging couples who seek a divorce at her job. Her sometimes aggressive tactics don't sit well with her clients as well as her superiors. She constantly visits a drive-thru, storefront church that seems to be in every other corner, to seek advice from a pastor. The god is silent on her questions and her husband's infertility and her faith is waning. Then a miracle happens. She is pregnant. But who is the father? Mascaro somberly reflects on life under the extreme right-wing, religious zealotry of Bolsonaro regime here. The film inserts in just enough details for us to see that the country has changed: women on the beach are wearing head to toe black garb - very much like burkini, every building, businesses and shops have customer identifying prompter at the door, by their name, marital status and whether they are pregnant or not. There is no mention or show of homosexuality whatsoever anywhere. In true Mascaro fashion, sex scenes are very graphic and honest, but only are limited to married couple or consenting adults and only heterosexual. The film is narrated by Joana's child who might be born out of immaculate conception and just might be the savior people have been waiting for, but left nameless and unregistered, because of he is born into religious fundamentalist country which was once was known as the most culturally, racially diverse country in the world that was Brazil, less than a decade ago.

Along with other countries in Latin America - Mexico, Argentina, Chile, Peru, Columbia and others, Brazil was battered with financial crises over the years, but the sound financial structure in place with natural resources, their recovery was quicker and better than the rest of the world. Combined with political stability of Lula years, Brazil’s cinematic output has become more diverse, sophisticated and technologically apt, compared with the films of Cinema Novo days. The intellectual hunger that Rocha talked about in his passionate declaration in The Aesthetics of Hunger, has been largely satiated and anger subsided. But every living organism needs to feed itself constantly to survive. The pang of hunger comes back whenever their stomach is empty. The neo-colonialism brought on by globalization with Bolsonaro helping, that hunger is rearing its head again and in it, the anger is again manifesting. As Mendonça Filho and Dornelles tell in an interview conducted in early 2020, Bolsonaro’s regime is already cutting funding to arts, putting a halt on film productions, compared with record number of productions that were happening in 2018. But I have no doubt that they will keep making films, as long as they stay hungry.

1. Braudy, Leo, and Marshall Cohen. Film theory and criticism: introductory readings. New York: Oxford University Press. 2004.

2. Chang, Dustin. “Interview: BACURAU Directors Kleber Mendonça Filho and Juliano Dornelles.” Screen Anarchy. March 13, 2020.

https://screenanarchy.com/2020/03/interview-bacurau-directors-klebermendonca-

filho-and-juliano-dornelles.html

3. Jeantet, Diane, “Far-right Bolsonaro fires latest round in Brazil culture war.”Crux, January 17, 2020.

https://cruxnow.com/church-in-the-americas/2020/01/far-right-bolsonaro-fireslatest-round-in-brazil-culture-war/

4. Lappé, Anna. “Follow the Money to the Amazon.” The Atlantic September 4, 2019

https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2019/09/follow-moneyamazon/597319/

5. Rocha, Glauber. “The Aesthetics of Hunger” [1965], in Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures: A Critical Anthology, ed. Scott MacKenzie (Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, 2014), pp. 218-20.

6. Solanas, Fernando and Octavio Getino. “Towards a Third Cinema: Notes and Experiences From the Development of a Cinema of Liberation in the Third World” [1969], in Film Manifestos and Global Cinema Cultures, pp. 230-50.

7. Shaw, Lisa and Stephanie Dennison, eds. Brazilian National Cinema. Routledge. 2007.

8. Stam, Robert. Film theory: An Introduction. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 2000.

9. Stam, Robert. Tropical Multiculturalism: A Comparative History of Race in Brazilian Cinema and Culture. Duke University Press. 1997.

10. Xavier, Paloma. “Vou ali num tal churrasco Bacuralizar’ brinca Silvero Pereira, intérprete de Lunga.” Uai.com. May 9, 2020.

https://www.uai.com.br/app/noticia/mexerico/2020/05/09/noticiasmexerico,258242/vou-ali-num-tal-churrasco-bacuralizar-brinca-silvero-pereirainter.shtml