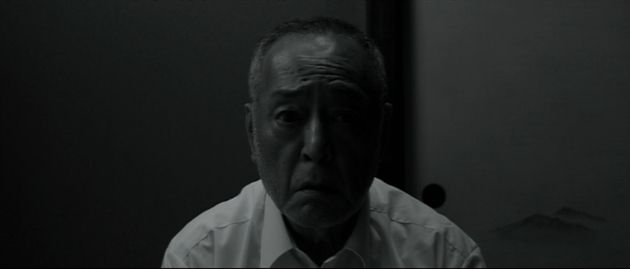

The Possibility of an Island, directed by the author of its source material, the Europe's premiere literary enfant terrible, Michel Houellebecq, even in this severely truncated film version, retains much of his theme nonetheless- our absolute aloneness, meaninglessness of human existence. But most of the venom and deviant sexual nature of the book are replaced by Mozart and Beethoven blaring soundtrack and uncharacteristic sentimentality, the film could easily come across as indecipherable, pretentious mess for the viewers who are not familiar with his work. What it does have though is some stunning locations doubling as the earth after apocalypse(s) and retro looking sci-fi sets that are reminiscent of both Tarkovsky and Renais. Daniel the hate spewing, womanizing comedian and a media celebrity in the book is gone. The social commentaries and banality of human life are only reflected (not so effectively) in the few scenes in the beginning with a bikini contest where a fifteen year old Russian girl shakes her booty in front of ugly old people in some mediterranean island resort that Daniel (Benoit Magmiel, looking like a hairless mole rat)is staying in. The Possibility concerns a religious guru (Patrick Bauchau) who promises eternal life with the backing of a scientist who finds a way to clone adult beings with one's memories and behaviors intact and with no dietary organs (they only need water and the sun to photosynthesize). Daniel is a reluctant follower and later becomes designated heir to the ailing guru. But after some hundred years, with everyone gone and no one to connect with, Daniel the clone no. 25 (in the book, never specified in the film) learns the life his predecessors led by reading ipad tablet like journals, finally gets out of his cocoon existence and embark on a search for a woman (Ramata Koite) or the idea of the woman the original Daniel once knew in a barren landscape.

With minimal dialog and rather ungraceful filmmaking, the film obviously doesn't have the same resonance of the book. But it's still an interesting Sci-fi with some gorgeous cinematography.