Hitchcock/Truffaut (2015) - Jones

We all know that everything has a meaning in a Hitchcock film - gesture, pose, framing, inanimate objects, camera movements, architecture, everything. It's layers upon layers of these cinematic elements that make his films stand the test of time. But to whom do we give credit for discovering this fact?

Surely there have been flow of books, articles, university courses, conference panels devoted to the master and his films over the last two decades or so. But it was François Truffaut, a film critic and French New Wave director of such films as 400 Blows, Shoot the Piano Player and Jules et Jim who interviewed his favorite filmmaker, the master of suspense, in 1962 and published the subsequent book Hitchcock/Truffaut in 1967 that really put Hitch among the echelon of cinema gods.

Truffaut, as a film critic, along with many of his esteemed colleagues at Cahiers du cinema (Jacques Rivette, Claude Chabrol, Eric Rohmer and more), had been the driving force behind elevating the status of many of the Hollywood Studio directors who were regarded as mere entertainers with the auteur theory under the guidance of the magazine's founder, André Bazin.

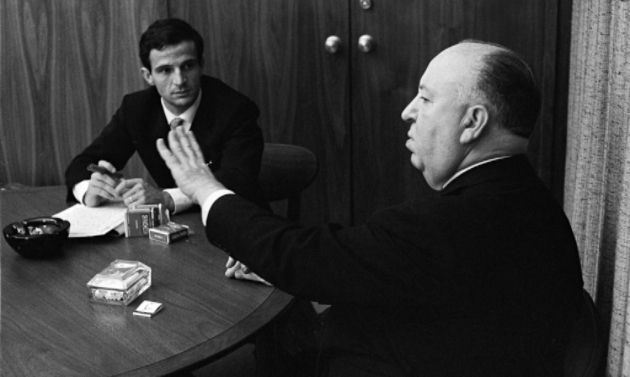

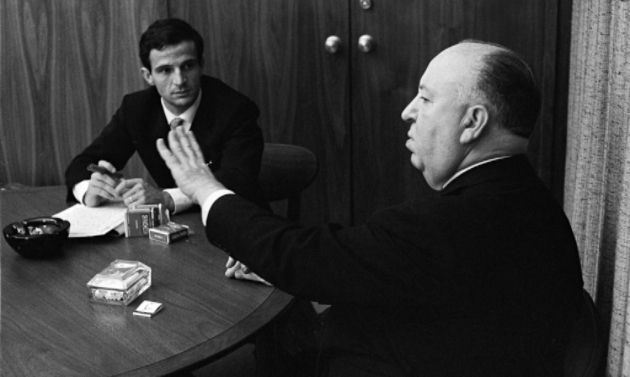

Hitchcock was already a one-man franchise in the industry and a TV personality with his weekly television show, Alfred Hitchcock Presents. But back then, he was never considered as a serious filmmaker nor he received due respect from anyone. Flattered by the attention given by Truffaut, Hitchcock took up the interview proposition and welcomed the young Frenchman in to his Paramount Studio office and granted a week-long interview. There, they discussed his filmmaking craft in great detail, one film at a time, going through his entire filmography.

Kent Jones, a film critic for Film Comment Magazine and a chief programmer for the NYFF documents the film companion version of this momentous meeting in cinema history, using film clips, audio recordings of the interview, and photographs taken by Phillippe Halsman at the studio and interviews with contemporary directors who are deeply influenced by the master in breezy 80 minutes running time. And it's a cinephile's wet dream.

Jones shows that going through his favorite filmmaker's entire filmography and asking pertinent questions, Truffaut was able to demystify Hitchcock the filmmaker, the man, the artist. Hitchcock's wrongly accused and guilty men alike stem from his Jesuit school upbringing and his fear of police. The interviewee in turn, was very frank and forthcoming about himself reflected in those characters, who had perverted secret desires and tendencies (hence the recurring motif of handcuffs and keys on both fear of police and secret desires).

Hitch Truff poster.jpgIt is a hard task to compress almost 13 hours of initial radio broadcast (out of 30 hours of actual recordings) of the interview and a 350 page book to a digestible feature length film and Jones is careful and considerate in what needs to be include in the film. He avoids the talk of obvious, well known Hichcockian narrative elements like MacGuffin or how many trick shots are in Birds.

Yet there are so many delicious morsels of information, aided by the film clips in Hitchcock/Truffaut. As the interview goes along, we get to see and hear examples of Hitchcock's craft: he answers that suspense doesn't have to come from the fear of violence with the clip from his early silent film, Easy Virtue: where a marriage proposal is only seen through the reaction of a switchboard operator- is she going to say yes, or no? Or insight to his view on actors and the role of the audience by giving an example of the kissing scene between Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant in Notorious, "They complained how uncomfortable that shot was. I didn't care if they were uncomfortable or not, I was giving the audience a ménage-a-trois with Ingrid Bergman and Cary Grant!"

Jones interviews contemporary directors who are as much cinephiles as they are filmmakers: Wes Anderson, David Fincher, Martin Scorsese, Paul Schrader, Olivier Assayas, James Grey, Peter Bogdanovich, Arnaud Desplechin, Richard Linklater and Kiyoshi Kurosawa. Many talk about their well-worn copies of Hitchcock/Truffaut on their bookshelf.

One of the juicy tidbits that are not present in the film from the vast audio interview sessions, is when he gets down and dirty on actresses: he tells Eva Marie Saint was terrible in North By Northwest, "She cost the studio a fortune for wasting films because I had to do so many takes." And that girl (Kim Novak) in Vertigo was 'no good'. He dismisses actresses who have sex written on their faces (Marilyn Monroe, Brigitte Bardot) because there is no more mysteries left in them. He prefers librarian types, "British women make the best Hitchcock heroines." At this, Truffaut protests, "I don't think majority of men will agree with you. And whether you realize or not, you are making them the standard (for sexual desire) with your films."

But Jones also includes what's not aired (I know this because I listened the whole French radio interview) when Hitchcock talks about famous transformation scene in Vertigo where Judy (Kim Novak) changes to Madeline at Scottie (James Stewart)'s incessant insistence: "When she comes out of the bathroom, Scottie has the biggest erection...don't include that.... Cut the tape!"

While Fincher seems very much tickled by the pervading perversity in Hitchcock films, the French directors - Assayas and Desplechin give insights to Truffaut's singular mission: He genuinely wanted to know all about Hitchcock because he was a fan. Assayas (also a former Cahier du cinema critic) points out that Hitchcock and Truffaut were much different from each other as filmmakers. Even though Truffaut was never a stylist, he always maintained that Hitchcock was his favorite filmmaker. Their amicable relationship continued through correspondences long after their conversations.

Perhaps Jones's biggest contribution here is in contextualizing their meeting and its impact in cinema history, thus also elevating the role of film critics (considering Truffaut was one) that, as raging cinephiles themselves whose respect and fanfare can reconfigure a certain filmmaker to be recognized as a great artist.

Thanks to Truffaut, much of Hitchcock/Truffaut is recognizing the genius of Hitchcock. The film glazes over Hitchcock's influence on Truffaut himself with only a couple of brief clips from his films other than 400 Blows without any voice overs. I wish Jones spent a little more time on Truffaut's filmography where we can see Hitchcock's influence. But still, hugely entertaining and informative, the film is a required viewing for any serious cinephiles.

Hitchcock/Truffaut Opens on Wednesday, December 2 at Film Forum and Lincoln Plaza Cinemas; December 4 in Los Angeles and December 11 in Major Markets Nationally