L'opera Mouffe (1958) - Varda

L’opera Mouffe is a 16 minute short film Agnès Varda directed in 1958 after her feature debut Le Pointe Courte. Pregnant with her first child, Varda made the film in her immediate neighborhood on rue Mouffetard, in the Fifth Arrondissement of Paris. It is a mix of observational documentary and avant-garde style, filmic diary of a pregnant woman. It is done in her irreverent, self-reflexive, hybrid filmmaking that she was known for all of her career. The tagline of the film is carnet de notes filmées rue Mouffetard à Paris par une femme enciente en 1958. It has a catalog-like structure with the title cards - The Lovers, Feelings of Nature, Pregnancy, Dearly Departed, Joyous Festival, Drunks, Anxiety, Cravings and so on. With the narration/singing, the film depicts the mind of a pregnant woman as she observes both lively and harsh daily lives of the inhabitants of rue Mouffetard.

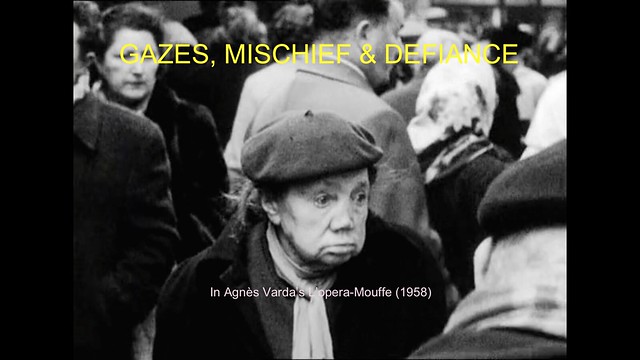

The film jumps around from one imagery to another. With loosely associated images and themes, L’opera Mouffe is a typical, Joyous and life affirming Varda film in a little package that showcases all of her usual themes and preoccupations in her later works - gazes, object/subject relationship, human bodies - especially female bodies, frank depiction of sex, aging and destitution.

Varda starts the film with her own naked, pregnant body. Her naked torso, seated against the black backdrop which accentuates her very large pregnant belly. There are many scenes in the beginning of the film with young lovers’ mingling bodies in various close ups- the contours, the crevasses, dimples & goosebumps. It is not the question of whether she was comfortable with showing nudes, as much as seeing the world through her perspective - “the world is defined by how I look and not how I’m looked at.” (Ince, 613)

The haptic visuality, which the eyes function as organs of touch, whereas optic visuality sees things from enough distance to perceive them as distinct forms in deep space, haptic looking tends to move over the surface of its object rather than to plunge into illusionistic depth, not to distinguish form so much as to discern texture. (Ince, 603)

Indeed, considering the next shot after Varda’s big pregnant belly are closeups of a giant pumpkin sliced up and its innards scraped out by an unseen farmer at the market. Through the deployment of a haptic gaze, Varda’s body - the filming and the filmed body - becomes here the feeling thing and subject-object Merleau-Ponty describes. It’s a self-portrait in haptic, rather than optical space. (Ince, 605)

Post-feminism constitutes a standpoint from which Western European female filmmakers disentangle their agency from unresolved issues in feminist praxis and theory: how to identify and develop feminine identity and expression within a society and a film system founded on male-dominant models of subjectivity. (Maule, 193) Throwing in her own naked, pregnant body first and foremost at the start of a film, Varda puts detractors questioning her as a feminist filmmaker to rest. And she did this in 1958.

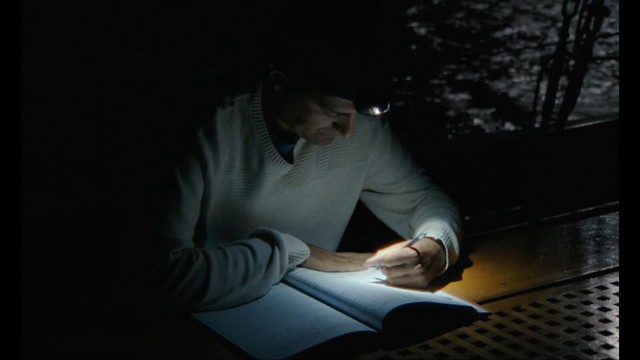

A simple narrative in L’opera Mouffe is a tale of young love. We see a young beautiful couple in the beginning: naked, embracing, smiling and making love in bed in their tiny habitat: A snapshot of a paradise in the biblical sense. The sequence is full of joy and happiness, directly contrasting the old and destitute habitants Varda films on rue Mouffetard.

The image follows the young couple’s happy thrist. Beautifully composed in the backyard of Varda’s dwelling on rue Mouffetard, with bare trees in the background, the nude female actor lies in a makeshift bed, looking at her reflections and smiling.

In Lacanian sense, the moment in which the infant looks at his reflection in the mirror is when the child develops a sense of self. Before this, the child doesn’t think of himself as an individual at all, but simply exists as a unified subject, as one with his surroundings. Therefore, the development of a sense of identity leads to a distorted image of true self. This reminds me of many of the mirror scenes in Varda’s filmography, most notably Cleo from 5 to 7 and Beaches of Agnès. In Cleo, when the protagonist first sees herself in the mirror, after being told her fate by a fortune teller, it is to reassure herself the sense of self. That she is still beautiful and that gives her the feeling that she is more alive than others. It’s that youthful beauty that says all is well. As the film progresses, with fractured mirrors, Cleo learns to leave her distorted version of self in the mirror and become free from how the society expects to see her as. In Beaches, Varda sets up multiple mirrors on the beach, as she walks on by and sees reflections of herself in multitudes of angle, suggesting a kaleidoscopic view of her 70 year career and life. The young couple disappears in the middle of the film, then reappears at the end to embrace, not only by themselves this time, but surrounded by the inhabitants of rue Mouffetard, in the middle of crowded street, suggesting that they go out of their own little world to face the real world while still keeping their love and harmonious relationship within the community.

There are many instances when Varda’s unsuspecting subjects on the street realizing they are being filmed and looking straight into her camera in L’opera Mouffe. This shot is not the first instance that happens in the film. They are both men and women. But more often than not, it’s the male subjects who wears intense displeasure on their faces.

It is interesting to think about Laura Mulvey’s notion of male gaze in cinema when viewing the film. In a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active male and passive female. (Mulvey, 837) The images of woman as passive raw material for the active gaze of man takes the argument a step further into the structure of representation, adding a further layer demanded by the ideology of the patriarchal order as it is worked out in its favorite cinematic form - illusionistic narrative film. (Mulvey, 843)

Again, considering Mulvey’s book was first published in 1975, Varda seems to be a way ahead of the curb in terms of her feminist filmmaking practice, defying patriarchal order of the world early on.

The ending sequence features a tracking shot of a visibly pregnant woman carrying a heavy load of groceries on the street. The title card reads “des envies” (cravings), followed by the shots of fishes in the outdoor fish stalls and various meat displays in butcher shop windows. The same woman stops by at the florist and starts voraciously devouring flowers. Perhaps Varda was commenting on weird cravings of a pregnant woman. But when we think of flower eating metaphors in art and literature, we think of lotus eaters in Homer’s Odyssey, an island tribe who are in a state of blissful forgetfulness. The term is often associated with people who indulges in pleasure and luxury rather than dealing with practical concerns. Many of Varda’s films, there are both sad and good moments, but all of her woman characters, there’s joy in being a woman and whether there’s a happy ending or tragedy with the choices they make for themselves. She quotes Simone de Beauvoir, “You are not born a woman, you become a woman.” (Kline, ed. 96) She explains woman’s prerogatives very nicely in an interview:

“If I enjoy pregnancy as a sexual event, it’s my life, my body! Many anti-feminist women don’t. If you choose to have children, pregnancy is a natural event, you should enjoy it. I’m not recommending the way the Church tells me to enjoy it, as a duty, or strengthen the state or the family. It’s never talked about, but most women actually enjoy sexy more when they’re pregnant, for reasons we don’t really understand. I supposed that has to do with many things. But should I deny it? World that make me a better feminist? A woman should let herself feel good being fat and full of baby, that’s her privilege. A model figure isn’t everything, and if that’s what you want, you can go back to it later.” (Kline, ed. 96)

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Ince, Kate. “Feminist Phenomenology and the Film World of Agnès Varda.” Hypatia 28, no. 3 (2013): 602–17.

Kline, T. Jefferson, ed. “Agnès Varda: Interviews.” University Press of Mississippi, 2014: 92-101.

Maule, Rosanna. “Beyond Auteurism : New Directions in Authorial Film Practices in France Italy and Spain Since the 1980s.” Bristol UK: 2008 :Intellect: 1-296.

Mulvey, Laura. “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema. Film Theory and Criticism :Introductory Readings.” Eds. Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen. New York: Oxford UP,1999: 833-44.

Freddie (Park Ji-min) is a young Korean born French woman in Seoul. She is staying at a hostel for couple of weeks. She is outgoing, impulsive and makes mousy Tena (Guka Han), whom she just met at the hostel and has been acting as Freddie's interpreter, very uncomfortable. It is slowly revealed that Freddie lied to her French parents to come to Korea to find her biological parents. Through the adoption agency, she gets a prompt that her father is willing to meet her. But no words from her mother. He lives in Gunsan a port city in the South West Korea, with his new family. And their encounter is pretty typical and cringey - Father and his family are extremely apologetic and eager to reconnect. Father insists that she relocate to Korea permanently and live with him. He will even find her a good Korean man to marry! It's all guilty conscience, over compensation and pure sentimentality. Freddie, irked by the experience and regretting her impulsive decisions, cuts the trip short and comes back to Seoul. But her father won't stop drunk texting her, apologizing and demanding. She has to put a stop to it.

Freddie (Park Ji-min) is a young Korean born French woman in Seoul. She is staying at a hostel for couple of weeks. She is outgoing, impulsive and makes mousy Tena (Guka Han), whom she just met at the hostel and has been acting as Freddie's interpreter, very uncomfortable. It is slowly revealed that Freddie lied to her French parents to come to Korea to find her biological parents. Through the adoption agency, she gets a prompt that her father is willing to meet her. But no words from her mother. He lives in Gunsan a port city in the South West Korea, with his new family. And their encounter is pretty typical and cringey - Father and his family are extremely apologetic and eager to reconnect. Father insists that she relocate to Korea permanently and live with him. He will even find her a good Korean man to marry! It's all guilty conscience, over compensation and pure sentimentality. Freddie, irked by the experience and regretting her impulsive decisions, cuts the trip short and comes back to Seoul. But her father won't stop drunk texting her, apologizing and demanding. She has to put a stop to it.