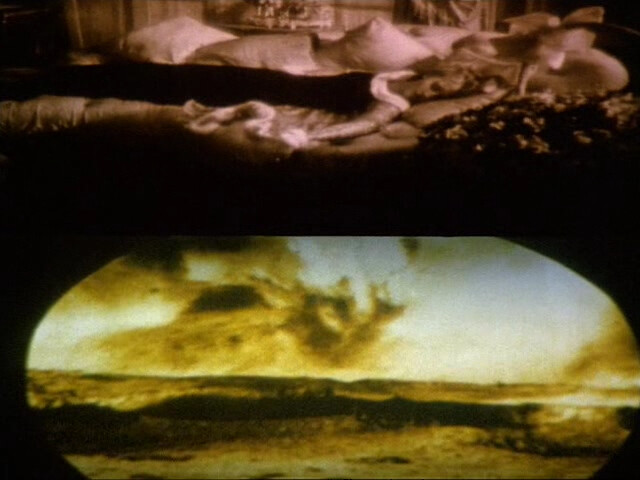

Just like his The Power of Emotion, The Assault is a jumble of short films taking on many different ideas. There is an interviewer pointing out a historian the stupidity of dividing world matters to 16 year intervals, a junkyard owner who get stumped by a philosophical questions about metal scrapes he's been producing, a chauffeur driving a businessman who makes a living making grave decisions all the time, there is a woman doctor who gets ousted by over equipped, mechanized, modern hospitals, a foster parent of an orphan girl hesitates giving back the girl to her opulent relative who doesn't really care about her, a family hooked on computer (internet), waiting for others to respond in front of it day and night and so on. The structure and method are pretty much the same as The Power of Emotions. There are operas, pinhole effects, narrator (Kluge himself) and stock footage of war and old movies. It's all heady stuff. People put too much emphasis on the present that they forget what came before it. They never learn from the past however atrocious it has been. We are always hurtling toward death anyway.

Kluge takes on cinema too. There is a bit about an old Polish couple in charge of The National Polish Film Archive, trying to save the place from Germans during its occupation by selling out their beautiful daughter to a German soldier. The last 1/3rd devotes to a story of a film director, played by Armin Mueller Stahl. He is struggling to answer why he is making a movie about a necrophiliac priest in the Middle Ages instead of contemporary stories. His eyes looking over yonder, he weakly responds that it's a love story, and that people weren't really capable of love in the middle ages. He turns out to be going blind and can't see his actors or whatever is going on in front of him. He has to rely on his assistants. There is a long sequence of a producer arguing over the phone, justifying why he needs to keep the blind director on the project. The reasons to keep him are just as good as the reasons not to.

The word that comes around frequently through out the many stories is superfluous. Kluge is an academical satirist who happens to make films. His films are layered and subtle. It never spoon feeds you with back stories or describing the motives of the characters and never laugh out loud funny. The film raises many questions about modern and often superfluous world we live in. I laughed out loud when he supposes that Film's been around only 90 years and it's superfluous, and maybe telephone will take over as a mode of communication. How right he was!