Malmkrog (2019) - Puiu

Cristi Puiu, a director closely associated with the Romanian New Wave, of realist films like The Death of Mr. Lazarescu and Aurora, take a very different approach with Malmkrog, a three hour twenty minute verbose chamber piece and a formalist cinematic daring-do that will certainly try patience of its viewers. Based on Russian philosopher's Vladimir Solovyov's texts in turn of the twentieth century, prior to WWI, Malmkrog's five main characters extensively engage in serious religious and political discussions in six chapters, named after the characters and István, the head of the servants in the wintry manor the film takes place in.

Cristi Puiu, a director closely associated with the Romanian New Wave, of realist films like The Death of Mr. Lazarescu and Aurora, take a very different approach with Malmkrog, a three hour twenty minute verbose chamber piece and a formalist cinematic daring-do that will certainly try patience of its viewers. Based on Russian philosopher's Vladimir Solovyov's texts in turn of the twentieth century, prior to WWI, Malmkrog's five main characters extensively engage in serious religious and political discussions in six chapters, named after the characters and István, the head of the servants in the wintry manor the film takes place in.

There are three heady discussions they are engaging in: war and peace, grand vision of unified Europe and the existence of good and evil. It takes a dramatic turn and there is a big tonal shift after the second discussion. The last one-third of the film could be interpreted as a dream or imagined but Puiu decidedly leave it opaque. Malmkrog starts out in a large, opulent manor in the middle of a wintry forest. The structure is in pastel pink, giving it a whimsical fairytale look at its first impression.

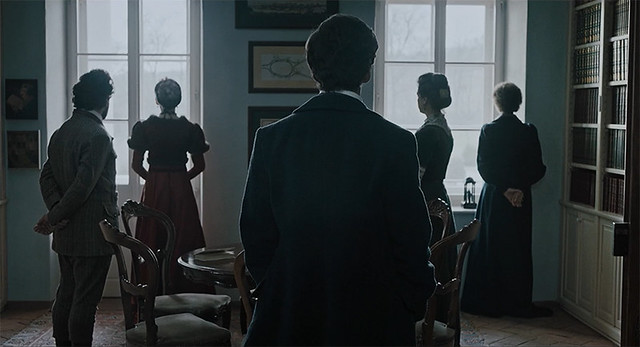

Inside, within very long takes in meticulous blocking, the actors crisscross the screen as they speak on and off screen. Camera pans slowly here and there, but otherwise it's stationary. Ingrida (Diana Sakalauskaité), a wife of a Russian war general starts the film with her indignant support for military might. There is a good war and there is a bad peace, she exclaims. Her view is pitted against the youngest member of this wealthy, aristocratic group, Olga (Marina Palii). Olga is a good Christian and a staunch pacifist. And because of that, she becomes a target of constant belittling, albeit politely, especially by Nicolai (Frédéric Schulz-Richard), a former seminary student and the host of the manor they are gathered at. The group splits in either defending Olga or chiding her. Ingrida receives and reads a letter from her husband announcing victory over Ottoman soldiers on the frontline. In a letter, he justifies slaughtering the enemies in the most grotesque manner because they roast babies in front of their mothers in the villages they raided. She enforces her assertion that the war is necessary. Olga disagrees. With her faith, she could've turned those 'savages' around by praying. Near the end of discussion just before lunch, in an intense interrogation in defense of her position on pacifism, Olga faints.

Lunch is served. They are back in another deep discourse. Edward (Ugo Broussot), a wealthy merchant and a gambler, espouses the grand vision of unified Europe. He says because Europeans are the most advanced, progressive, therefore they are superior civilization. And Russia can play a big role because of its proximity to Asia in fending off the influence of Asian nations. Then the discussion turns to the existence of good and evil with Nicolai chiding Olga with her interpretation of the bible verses.

Of course, in accordance with the era and society, all dialogue is conducted in very proper French. Only other language spoken (very briefly) is German, when Nicolai cryptically whispers to Olga travel paths. Did he see what was coming? Is he planning an escape with the young believer?

As the second discussion draws to a close, a drastic incident happens to break the otherwise tranquil gathering of the high society: a broken childish song that sounds like coming from a gramophone plays in loop all of sudden and all the servants disappear or not answer Nicolai's ringing bell. Panicked, our guests leave the room only to be gunned down from an unseen force. Next scene is a wide shot of the snowy landscape outside and people calling out Ingrida, who seems to be treading the snow away from the manor. Puiu keeps everything ambiguous from beginning to end.

The next scene is business as usual. All the guests seem to be alive and well and carry on the subject on good and evil. How do we know that god is good? He can preach us to be good. But is he himself good inside? Olga is pushed to defend her positions. She seems composed but not able to speak anything remotely compelling. This dinner scene with five characters speaking back and forth, is a fine example of how you do coverage and make Bohemian Rhapsody's Oscar winning editing to shame.

I don't doubt that Malmkrog's script being as thick as Dostoevsky's Brother's Karamazov. It deals with dense, heady philosophical musings from another century. But context is everything. What these characters are discussing has relevance in pre-revolution, WW1 Europe as well as the age we are living in.

Veering off the Solovyov's texts, Puiu reinforces its prophetic, dystopic view of Europe - decadent, spiritually hollow, hubristic, jingoistic and also on the cusp of violent upheaval. Puiu being Romanian, growing up in a country in the Soviet Bloc, Solovyov's texts are a good fit for him against anti-spiritualism associated with communism along with many other ills Europe and Russia are suffering right now.

Malmkrog is a slog of a movie. But it’s truly one of a kind. If you are an adventurous spectator like me and stick to it, with a bit of background knowledge beforehand, the film is a very rewarding and satisfying cinematic experience. This will make a great double feature with Lázló Nemes's Sunset, as a frustrating yet richly rewarding cinematic history lesson and a prophetic vision of Europe.