With plenty of evidence of the decline of Western Civilization presenting itself on TV news these days, NYAFF (not to be confused with New York Asian Film Fest) , in it's 25th year, with more than 30 films on its slate, criss-crossing 3 of New York's venerable film institutions (FSLC, BAM and Maysle's Cinema), gives filmgoers a chance to experience fresh perspectives on the world.

This year's festival includes new films from emerging filmmakers, shorts programs, revivals, panel discussions and an art exhibition.

Opening Night will spotlight Apolline Traoré’s award-winning film, Borders, which speaks to migration as well as to African women’s struggles, in a timely echo of the #MeToo movement. French director Berni Goldblat’s Wallay will have its New York premiere as the festival’s Centerpiece film.

The festival tips a hat to key figures in the history of African film with the U.S. premieres of Abderrahmane Sissako: Beyond Territories, Valérie Osouf’s intimate portrait of the acclaimed director of Bamako and the Oscar-nominated Timbuktu; a 2017 version of the 1983 classic Selbe: One Among Many, by Safi Faye, the first sub-Saharan woman to direct a theatrically released film, now restored to its original Wolof language; and Mohamed Challouf’s Tahar Cheriaa: Under the Shadow of the Baobab, which documents the career of the founder of the Carthage Film Festival, Africa’s first film festival. The festival will include the 1989 documentary short Parlons Grand-mère by the late Senegalese director Djibril Diop Mambéty.

These are the dates for this year's New York African Film Festival:

FSLC: 5/16 - 5/22, Brooklyn Academy of Music: 5/24 - 5/28 & Maysle's Cinema: 6/7 - 6/10

Make no mistakes, below outstanding, touching, funny, powerful and hopeful films are definitely not made in shithole countries:

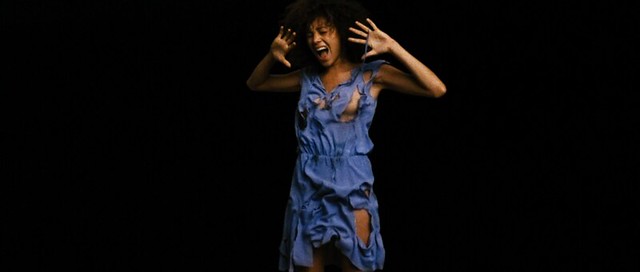

Borders - Apolline Traoré *Opening Night Film

Adjara, a Senegalise woman with her savings in her waste bag, travels to Lagos, Nigeria in the hopes of becoming a trader. Along the way, she meets 3 other female travelers in various situations.

This six day journey from Senegal through Mali, Burkina Fasso, Benin to Nigeria is an arduous one as they face rampant border corruptions among the sub-Saharan countries, violence, rape and fighting with other passengers, shady transportation and breakdowns.

Borders highlights pan-West African sisterhood and imagines the better future for its female citizens.

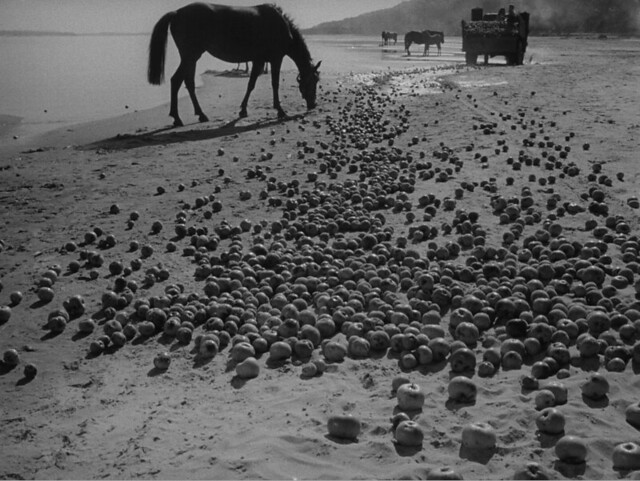

Wallay - Berni Goldblat *Centerpiece

I've seen quite a few films over the years about a troubled youth going through right of passage visiting and connecting with his/her ancestral homeland, but none as funny and touching and joyous as

Wallay.

Wallay takes place in small village in Burkina Fasso, where Ady, a troubled 13 year old city kid from Paris is sent to by his father, after stealing money from his home to buy a shiny pair of red sneakers. Decked out in street gear, an iphone and fancy headphones, the spoiled brat faces reality of no electricity and two buckets of water per shower in the African village. Add to this unimaginable hardship, his uncle Amadou, a respected village elder, is a hardass and wants him to work on a fishing boat for 2 euros per day to pay off his debt. Not only that, after finding out Ady is not circumcised, the uncle wants the local doctor to perform circumcision on the boy to make him a real man.

At Amadou's urging, Jean, Ady's grown up distant cousin and a guide, takes the boy to meet his grandma who lives in a remote mountain town. Ady becomes grandma's instant favorite who calls him 'Little Hubby'. With the help of 'chilled out' grandma, Ady slowly learns the importance of family, discipline and respect. He gets to experience a bit of romance too with Yeli, grandma's little helper.

Shot beautifully on film,

Wallay benefits from amazing performance by Makan Nathan Diarra as Ady, an insolent city kid with an attitude, slowly turning himself into a man. Goldblat doesn't rely on its spectacular locale or its customs, he doesn't have to. The story of Ady is universal enough. Everything plays out naturally. Hugely captivating and entertaining,

Wallay is one of the best films I've seen this year.

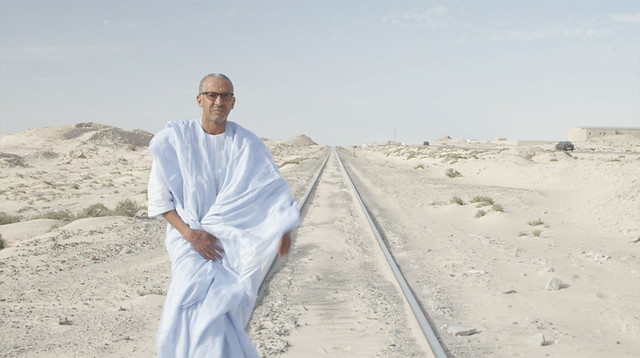

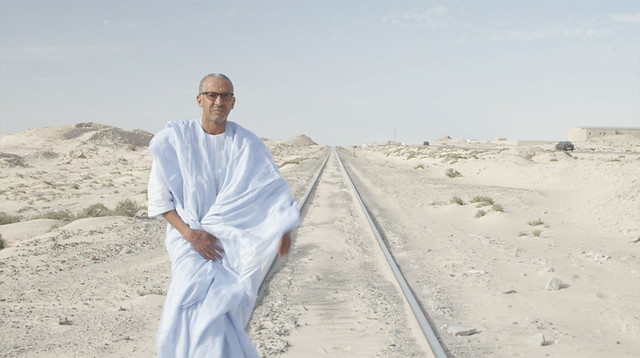

Abderrahmane Sissako: Beyond Territories - Valérie Osouf

Valérie Osouf's documentary on one of Africa's most revered filmmakers, Abderrahmane Sissako, is not only an intimate portrayal but an essential viewing in understanding the man behind the camera. Widely regarded as a modern day master filmmaker with his simplicity, directness, colors and movement in films like

The Life on Earth,

Bamako and

Timbuktu, highlighting the lives of fellow Malians in the age of global capitalism and ISIS, Sissako elevated modern African cinema to the world stage. Thankfully, with the help of Western admirers - Martin Scorsese and Danny Glover (both are interviewed for the film), he keeps on making gems reflecting the world with Africa at its center.

In an informal open house setting, Sissako invites and talk with everyone - a film enthusiast cop, a philosopher, scholars, actors, dancers while the life is happening all around them - roosters walk across the court yard, children play around, a woman gets water from the well. His background gets revealed - from his Moscow film school days - his mentor Marlen Khutsiev reminisces that he knew Sissako would be a great filmmaker because he noticed his thoughtful gaze when they first met. He gets his intellectual side from his father's family and warrior side from his mother's who are from very different parts of Mali, therefore his deeper understanding of different cultures.

The last segment of the film takes place in China, where he's researching for his new film, a love story about a Chinese man and an African woman, tentatively going to be taking place in China, Ethiopia and possibly Nigeria. He chats with his good friend Danny Glover over skype about his project. The film ends in an optimistic note. The influence of China is already felt globally. But Africa can't be recolonized. Connecting these elements, it's more like Silk Roads connecting different worlds with mutual respect than one side dominating the other.

As we witness the obvious decline of Western civilization every day, I can see Sissako's vision and it's pretty bright.

*My interview with Abderrahmane Sissako last year

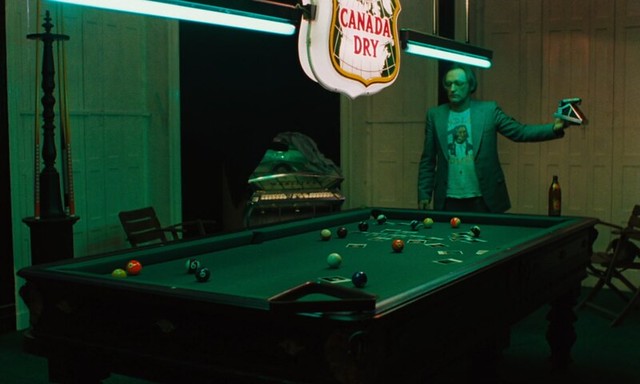

Five Fingers for Marseilles - Michael Matthews

Marseilles is a railroad town in South Africa which still bears the name of its colonial days. Michael Matthews' sumptuously shot Western

Five Fingers for Marseilles starts with 5 young friends making an oath to protect their town as freedom fighters, even if it means from each other. Tau, nicknamed Lion of Marseilles, one of the five, flees town after killing corrupt and abusive white police officers, leaving his friends and lovely Lerato behind to fend for themselves.

Now a grown man and a small time outlaw, Tau (Vuyo Dabula) comes back to town. The 'New Marseilles' is a booming town with Pockets, one of the five friends, as a mayor who is keeping uneasy peace by making pact with Lepoko - a ruthless, one eyed super-villain who wants to bring chaos at any cost with his marauding gang known as Nightrunners. No one notices Tau, and start calling him 'Nobody' except for 'Pastor', a storyteller of the five. As the Lepoko's grip on the town becomes tighter, and everyone needs a savoir, Tau, the cowardly, disgraced freedom fighter rise to the occasion?

Just like a typical Western genre film, there will be bloodshed, sacrifices will be made, reckoning, redemption.... With the stunning backdrop of Lesotho Valley, Matthews morphs post-apartheid South Africa into a gripping Western.