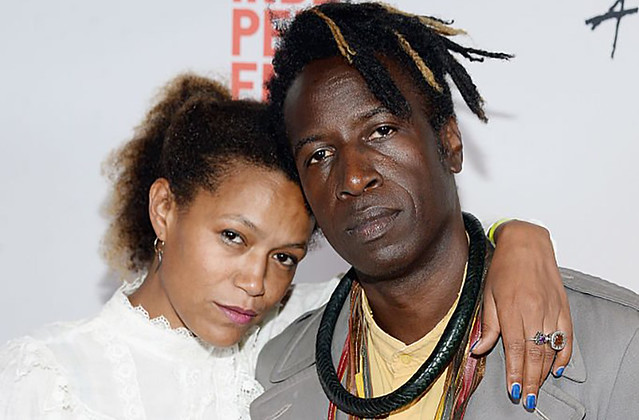

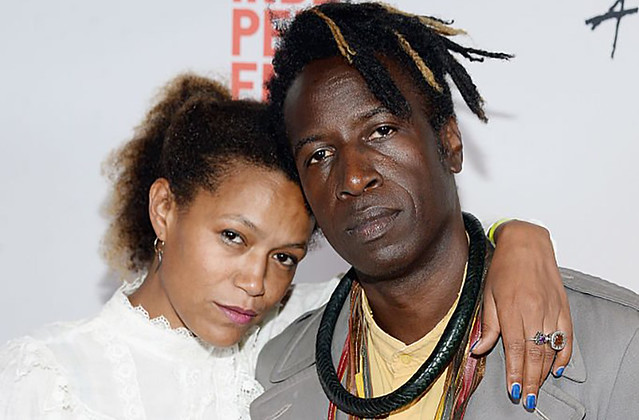

Neptune Frost, an Afrofuturist musical directed by multidisciplinary American artist Saul Williams and Rwandan visual artist Anisia Uzeyman, is a stunning film that defies conventions both content and form. When I saw it in a packed theater at New York Film Festival last year, I was enraptured by its sheer beauty - the DIY aesthetic, from the costume design to production, and its languid visual language. Then I was impressed by its very progressive politics - a non-binary superhero emerging and resistance movement against neo-colonialism.

I am very happy to see the film getting a theatrical release, thanks to good folks at KinoLorber, because Neptune Frost needs to be experienced visually and aurally on the big screen and talked about for the years to come.

Crowd-funded, the long arduous journey of production of Neptune Frost is something that needs to be looked at, concurrently with the release of the film, as an example of sheer will power and enthusiasm of its creators and everyone involved. I am very happy to bring you some of these backstories and more by having a chance to interview Williams and Uzeyman last week. So without further a do:

Saul and Anisia, thank you for talking to me today. I watched Neptune Frost at last year’s New York Film Festival and with a packed audience and was totally blown away by it. It must been such a monumental task and I don’t know how you pulled it off, but it was an amazing experience.

Saul Williams/Anisia Uzeyman: Thank you!

I understand you met each other on the set of Tey, directed by Alain Gomis, a Senegalese director’s film, as actors in 2012, am I correct?

Williams: Well actually we met at Jean-Michel Basquiat’s exhibition in Paris. It was even before Gomis film. And everything started from there. The desire to work together or collaborate came very early and the idea of this film, which didn’t start as a film but a stage play, a musical and as a graphic novel. Because both of us are actors, we wanted to create something that we can both act in, but when a producer, Steven Handel who produced Fela! On Broadway, read what we were putting together, told us that he loved the story and suggested that it would make an extraordinary film. We eventually realized that, as a film, it would shift and open much more possibilities, because here is a story that according to our writing that it would take place in Burundi and what have you, suddenly the idea of that we can go on location to shoot, the excitement about meeting all of the new faces and new actors and new talents - what it would mean for all the other artists whom we can bring in. But we had no idea what was in store for us when we accepted the idea of making a film. We hadn’t met our costume designers/set designers, Cedric Mizero, not until we went to Rwanda in 2016 to shoot a test.

Anisia Uzeyman: So we thought of the film taking place in Burundi but in 2015, Burundi kind of went through a lot (with the violent political, civil unrest), so it became a complicated location for shooting. But the idea of shooting the film there felt more liberating in terms of how our imagination went. So we went to Rwanda in 2016 to see how things were there. You know it’s the same landscape of hills and so on and there’s a lot of connection between the two countries. So we arrived there and met a lot of Burundian activists because of the flow of refugees fleeing the situation in Burundi.

Williams: 2015-2016, just as we were arriving.

Some two hundred thousand refugees?

Uzeyman: Yes. All these young people - students, activists, artists, fled the country and into Rwanda. It was this alignment of what you dreamt and what you found there that allowed us to say, “OK, this is the place!” It was synegistically clear.

Something that clicked in you, during that trip.

Williams: Yes. The first week of that trip, we encountered the majority of our cast. We also met Cedric Mizero our costume and set designer, and within the first conversation with Cedric about what the project was about, he was like 21,22 years old then, he understood immediately what we were doing. He came back the next day with sandals made of motherboards.

Oh wow.

Williams: and we said OK. This is it. We found the right person and we found the right people. Everyone introduced us to each other and the excitement in the story we were telling–

Uzeyman: And we also met the ensemble.

Williams: Yes, we also met the drum ensemble. They were refugees from Burundi who crossed the border with their drums, taking refugee in Kigali.

Uzeyman: That’s when we met Kaya Free who plays Matalusa. So we met almost everyone in the cast pretty early on. I told Saul to come and see these people and how to incorporate all these people and music and so on.

There are a lot of languages spoken in this film. When you composed the music, was it planned that way or was it something more fluid, a collaboration among all of the artists instantaneously?

Williams: So this is kind of a simple answer to your question. In that region of the world, when you are on the ground, what you find is that everyone speaks about 5 different languages. When you are sitting down at the table having conversation, they’d use expression that works best with each language. So we might say something in French or Swahili or Kinyarwanda or Kirundi and after a while we go, 'fuck this'. Me I speak English and French and I get certain words that might come through… the thing is, it’s extraordinary how we can communicate this way. All we wanted for the film was to reflect that. That’s why it’s like that. It’s not like bringing in a specialist to translate this or that language, it was naturally occurring. Our cast members naturally communicated with each other in many languages regularly. I remember going to karaoke in Kigali, Anisia’s people would be like, I want to sing this song from Mexico or this song is from Congo and this is from France. No one was flexing or showing off. They just knew that Spanish song, they knew that English song… It was just normal to them.

Uzeyman: This is very much so to the region and its history. It is also very much the case with fluidity of our culture as it expands as we open ourselves to the world.

I was going through the list of cast and crew and most of the names are not European or American, even though you both have connections in Europe and America as artists. Was it a conscious decision to employ local artists?

Williams: Yes. It was an extremely conscious decision to work with, both cast and crew locally and to bring in as few people from outside. It is true with a lot of different production companies with foreign money - European or American money, they fly in everybody and Rwandan people would be third and forth assistants. And we thought it was important to have local people heads of the departments. It was crucial to us. Secondly, there is no cinema rental facilities in Rwanda. So just because of our finance and what have you, we had to choose between spending all our resources to try to ship in all the lights for example, or build them.

DIY style.

Williams: It was easier to build our cinema lights and LED panels, dollies and 18 kilowatts cinema lights and even apple boxes. Everything you see in Neptune Frost was built by the crew. That was part of the excitement as well. We were not going in there like European or American film crew…

Uzeyman: We are from there. Simply because I was born there and Saul was adapted. (laughs) That’s why we did everything with our community. It was our desire to share the experience as a communal experience.

For those who don’t know about MartyrLoserKing Project. Can you tell us a little bit about that and its connection to Neptune Frost?

Williams: This whole project was born out of multimedia conceptualization. And so we were telling the same story as a graphic novel, as a stage play, as a musical and through a music album. As I mentioned, it was transition from musical to film- the graphic novel is still coming out next year. It's a surprise to us that our film is beating the graphic novel, but you see unlike the long list of names working on the film, there will be one or two illustrator and the writer for the graphic novel to tell that story. (laughs) Neptune and the hackers as a collective is known as MartyrLoserKing which we learn as it happens in the film. The biggest difference is that in the graphic novel, we see a little more from the MartyrLoserKing, the hackers collective's and the miners' perspectives. You see more of Techno’s perspective, you see more of that. It’s because there’s a lot more backstories in many of these characters. In the film there’s visual and there’s music and there’s a lot of space for you to explore and contemplate. But in the graphic novel, there’s a lot more texts.

That’s great. Already there’s a lot of layers in the film but there are a lot more to those characters and I am happy to hear that there will be more of them in the graphic novel. I think it’s also interesting to hear how you put all these elements together.

How I processed Neptune Frost and how it all clicked together is from the very beginning - the sound of the miners with their hammers and pickaxes digging and their singing were very similar to how American railway was built on the backs of African slaves and how the blues came about - that everything is cyclical with this global economy and rebellion and exploitation of resources and exploitation of the black bodies.

Neptune Frost is played first by Elvis Ngabo, then Cheryl Isheja. With this non-binary, intersex idea with all the young people involved in this project, you think it’s the future of humankind? Is that the message?

Uzeyman: Definitely. I think discussion on gender is ongoing. I think young people are fatigued by the old way of thinking and rightly questioning the patriarchal, empirical, the neo-colonial societal norms and this pushes people to find way to be more open and to liberate themselves from that thinking.

Williams: Yes. I mean, it’s our intention to through this film to be part of that dialogue, to provide working examples to be a part of that very modern dialogue that is crucial, to our understanding of each other, to the freedom and excitement of the new generation has and realizing the importance of being themselves beyond what they are assigned or being who they were told to be and who they were told they are.

Uzeyman: I think it’s so courageous also and I think it’s a kind of revolutionary moment that we are witnessing and being part of, in the desire of transforming, of refusing the status quo of the hierarchy of unfair and brutal society. It's not so much that we were projecting this with our film this is the discussion that’s happening right now.

Williams: And you see the pushback, you see the people trying to maintain a certain level of rigidity. It’s important that it’s not only the future but also the past - the colonial imprint that was heavily placed on people’s necks. That rigidity has put people lining up on the borders and the confines of the prison of rudimentary, heteronomative, binary definitions and–

Uzeyman: And people realize that it only starts with you.

Williams: Exactly. It affects everything. You asked about the fluidity of language. People on this side of the ocean were like, “You know how much money we are losing for not having the film in English?” When you're talking about seeing that it’s all connected that there is binary connection on every level and these rigid boundaries are placed on expression. So the authenticity of it and expression like you see in this film would automatically be thrown out. Why? Because there’s no famous people in it and it’s not in a language people of this country speak. There’s so much. It’s not only what we were doing on screen there. But every conversation, every experience we had in every festivals that everything we encountered to, just reach an audience to see the film has been a fight. It was intentional with its time. It was last year and the year before when we were talking about black bodies exploited, we were talking about BLM movement, transgender rights. We said, well here is something that is in conversation with that conversation. How do we respond to that, how do we support that? How do we uplift that or do we just go on to perpetuate the same cycle- the same bullshit, the same violence, the same bigotry, the same rigidity in our creative choices?

When we talk about Afrofuturism, how it provides not just mere escapism but a space to have this kind of conversation and exchange these kind of ideas. Do you think it’s possible to make films like Neptune Frost only in Africa - just because the wealth of cultural, social upheavals are happening there?

Williams: I’d say not at all. I need to hear from the people who are working in mines of China, Brazil, Peru, in Bolivia–

Uzeyman: We just saw a beautiful film from Bolivia.

Williams: It was about young miners. What was it called…

Uzeyman: ...and there was wonderful music in that too. It was El gran... it will come to me…

El Gran Movimiento! A great film!

Williams: Yes! So no. We at one point was thinking about shooting the film in Haiti. Our research brought us to shoot all over the world. The story of Neptune Frost- the exploitation of workers, the role of authority, belongs to the workers of the world. Those workers are still in Ireland, in Thaliand, in Cambodia. So no. I think Africa is a wonderful place for our story to be told, but for all the other places, there’s need to see and connect with those group of humanity and resources so we can share them. Yes, so at the same time, the story belongs to many, many people.

Uzeyman: Neptune Frost is kind of a retelling of a folktale, a fairytale, a birth of a superhero, right? It’s a journey of that person gaining their power. It’s just like any other superhero story. I’m pretty sure you will find that there is the same narrative everywhere.

Williams: Yeah, it’s a shared history. As you stated that while watching the film, you are connecting the dots. So yes, indigenous people of many lands can connect those dots and see themselves in this film. And that’s the first layer of what this film is about. It’s them realizing that their land is mined for power. Their land where they think and dream and birth and work on, is the power in us. Do we have that power? Are they mining our ancestors that we buried? Is that what’s affording them to communicate wirelessly? Is that our power? And Neptune is saying, yes. And that realization can be shared throughout the planet. Of course, it belongs to many.

This has been an amazing. I can’t thank you both enough for this conversation. Everyone needs to see this film on the big screen. BIG SCREEN.

Williams/Uzeyman: Yes.

Neptune Frost opens in theaters on June 3rd in New York and June 10th in LA. National rollout to follow.

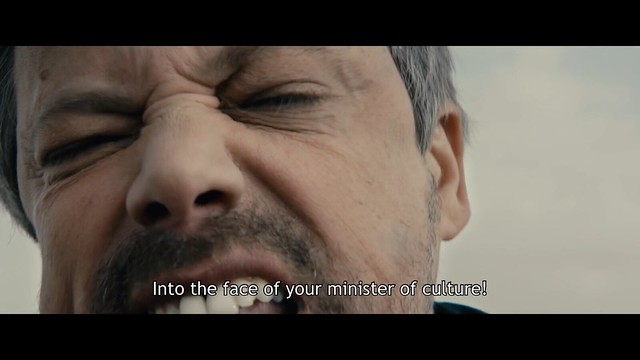

Unlike its ironic title in Michael Haneke's searing portrayal of bourgeois French family, no one is quite happy with their lives. An aging patriarch of the house Laurent (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is quietly suicidal with his failing body and early Alzheimer’s. His daughter Anne (Isabelle Huppert), the head of the family construction business, is facing a lawsuit by a worker involved in an accident at one of the construction sites, which is shown in CCTV camera in the beginning of the film, and her grown up son Pierre (Franz Rogowski) is not good at anything and not ambitious enough for her despite all the pestering. His son Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz), a surgeon, is having an illicit sexual affair with a musician while neglecting his second wife and a newborn baby. Then there is Eve (Fantine Harduin), a thirteen-year-old girl from Thomas's first marriage. She comes to live with the Laurents after her mother is hospitalized for poisoning (Eve secretly poisoned her mother and recorded the process on her phone for amusement).

Unlike its ironic title in Michael Haneke's searing portrayal of bourgeois French family, no one is quite happy with their lives. An aging patriarch of the house Laurent (Jean-Louis Trintignant) is quietly suicidal with his failing body and early Alzheimer’s. His daughter Anne (Isabelle Huppert), the head of the family construction business, is facing a lawsuit by a worker involved in an accident at one of the construction sites, which is shown in CCTV camera in the beginning of the film, and her grown up son Pierre (Franz Rogowski) is not good at anything and not ambitious enough for her despite all the pestering. His son Thomas (Mathieu Kassovitz), a surgeon, is having an illicit sexual affair with a musician while neglecting his second wife and a newborn baby. Then there is Eve (Fantine Harduin), a thirteen-year-old girl from Thomas's first marriage. She comes to live with the Laurents after her mother is hospitalized for poisoning (Eve secretly poisoned her mother and recorded the process on her phone for amusement).