An epic melodrama spanning 17 years, Jia Zhangke's new film, Ash is Purest White, harkens back to the Chinese auteur's earlier films. I say this not just because it mostly takes place in Shangxi province (the director's home province where he made 3 of his early films), but also because he abandons the episodic/omnibus storytelling of Touch of Sin and Mountains May Depart, two of his last films. Instead, he concentrates on a long and arduous relationship between Qiao (Zhao Tao, Jia's long time partner in crime) and Bin (Liao Fan of Black Coal Thin Ice). Ash can be seen as the compendium of 48-year-old auteur's filmography and its 144 minute running time can feel like a slog at certain points. But it's one of those films that gains strength and poignancy over time and certainly is the future classic in the making. It's definitely his most mature film to date.

The film starts in Datong, the nothernmost area of the director's home province Shangxi. The year is 2001. Qiao is seen in full frame video shot footage instructing dance moves in a dance hall. With her bangs and youthful looks, this footage might as well be from Unknown Pleasures (which came out in 2001). She enters the majong parlor, and it's in 1:85 aspect ratio (they used several different formats for varying degrees of success). She is the squeeze of a local low level mob Bin, who runs a majong parlor. It's a dangerous business and there are competing younger mob factions ready to take him and his men down when given an opportunity. Times are a changing.

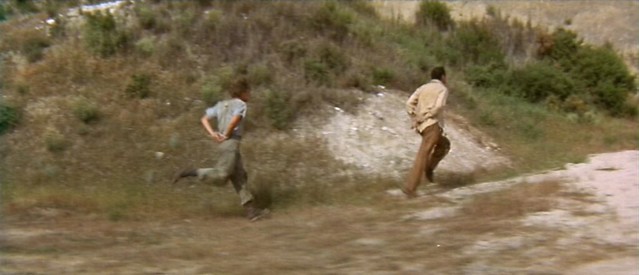

Bin brings Qiao to a field which saw volcanic activity thousands years ago, to teach her how to shoot a hand gun. It's an unregistered, illegal gun he acquired. The Chow Yun Fat-starring Hong Kong action movies had a bad influence on Bin and the rest of his generation. He mentions that the ashes from the volcanic eruption is the purest white, foreshadowing the rapid change in China, where anything old is demolished, buried or drowned for the new generation. A clean slate. A new beginning where no regrets, no tears, no sentimentality are allowed.

After a hit on Bin's crew sees him fatally attacked, Qiao fires the said illegal gun to save his life and is sent to jail for 5 years. Now it's 2006, and Qiao is out of jail and looking for Bin. He never visited her in jail and has moved to a town near Three Gorges dam. So this is where the road movie of Qiao starts: she meets various characters on the road/river with the rapidly changing nation in the background. The technology has changed appropriately, the fancy office buildings go up, all sorts of business ventures spring up. But people, the flood of people, trying to eke out the living with the changing times and circumstances, remain the same.

Bin, with a new girlfriend, refuses to see Qiao. Heart broken and with nowhere else to go but back to Datong, she almost agrees to go with a new venture capitalist whom she meets on the train, to the west. Decisions we make in our lives, good or bad, would lead to a different life than where we are right now. But how much can we deviate from our natural instincts, our traits, our character?

It's the New Year, 2018. Qiao finds Bin back in her life in Datong. He's had a stroke due to excessive drinking and is now a wheelchair bound. Qiao, who never married, silently takes care of him. He throws a fit sometimes, reliving his jianghu (underground gang) days in his head. She doesn't let him go off though. Is he ever going to change?

Ash is Purest White is a full-on (un)sentimental melodrama in epic scale. It's perhaps Jia's most down to earth, character study work. The long stretch in the middle gains more poignancy as the film goes along and afterwords. Some people reinvent themselves along with the changing times and some people don't. Some things in them though, remain the same. Jia expertly juxtaposes these conundrums, reflecting the soul of a changing nation. Ash is the Purest White is a deep and poignant masterpiece from a seasoned filmmaker.