Roma (2018) - Cuaron

Alfonso Cuarón, a director known for his meticulously crafted Hollywood sci-fi movies Children of Men and Gravity, goes back to his native Mexico and gets more personal with Roma, based on childhood memories of his nanny. It is his first Mexican film since Y Tu Mamá También in 2001. The result is a well-balanced, mature, humanistic and highly subjective observation of a woman’s life.

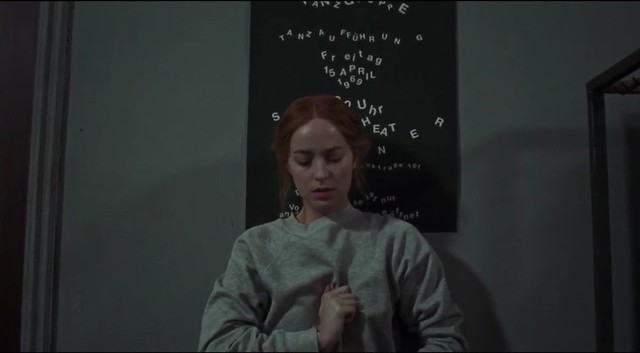

We are introduced to Cleo (Yalitza Aparicio), an indigenous woman working as a housemaid for an upper-middle-class family in Mexico City. Shot in sumptuous black and white, large format (instead of getting help from his regular DP Emmanuel Lubezki, Cuarón shot the movie himself) and using subtle unassuming techniques (mostly in wide angle, slow pan and tilt), the movie focuses on the life of a woman and her profession, which is seldom a subject for a major motion picture.

We start with a long, static shot of the stone floor of a narrow, gated driveway being washed. We hear sounds from the lively neighborhood – dogs barking, children playing, various street sellers signaling their arrivals. The sudsy water is thrown over and over, and we see a plane going across the sky in its reflection on the floor. After the initial title sequence, we slowly tilt up to reveal Cleo doing chores in the courtyard. With this opening, Cuarón sets up the rhythm of Roma – the steady, forward march of time. We are about to witness for a little more than two hours the trials and tribulations of Cleo, the house servant, within a year’s span. The year is 1970.

Cleo and Adela (Nancy García García) are two live-in housemaids for Señora Sofia (Marina de Tavira) and her mostly absent husband, her old mother and their four rambunctious children. Cleo and Adela wake up before everyone else, cook, wake the kids one by one, get them ready for school, clean, wash, get groceries, carry luggage, make tea and do everything else in between. It is clear that much love is shared between the family and Cleo. Kids love her and say so often, and Cleo does too.

Sofia goes through a tough time dealing with the fact that her husband is cheating on her – he fakes business trips to Canada when in fact he is staying in the city with another woman. She appreciates all Cleo does but also lets her know her place on occasion. Cleo is part of the family but not quite: in one continuous sequence we see the whole family viewing a TV program together. It is some silly comedy and everyone is watching and laughing. Cleo, while mindful of everyone’s needs, watches and laughs with them. She approaches the couch where the kids are sitting and sits down on the floor next to them. One of the kids leans his head on her shoulder. Sofia tells her to go and make some tea. She gets up and goes to the kitchen.

Cleo gets pregnant by Adela’s cousin Fermín (Jorge Antonio Guerrero), a brash martial arts practicioner. He abandons her as soon as she tells him that she is pregnant. Sofia, perhaps feeling the sisterhood of abandoned women and/or out of the goodness of her heart, embraces Cleo’s pregnancy and pledges her support.

It is the small details Cuarón shows us that have a cumulative impact, like the sequence of the father very carefully parking his oversized car in the narrow driveway, the constant presence of dog shit on the floor, a plane flying across the sky…. With Roma, he doesn’t make a broad political or cultural statement. It is not that Cuarón ignores the social stratification or political climate in Mexico during 1970 and 1971. Quite the contrary – the family Christmas getaway in the mountains, at the opulent mansion of one of Sofia’s friends, reinforces the masters-and-servants relationship as they have separate living quarters and hangout areas. This is also where we get the only clue to Cleo’s background as she muses on the barren landscape and tells her friends, “This is what my hometown looks like. Drier than this though.” Then there is the Corpus Christi Massacre in 1971 where government thugs (known as Los Halcones) shoot and kill 120 protesting college students. The chaotic scene on the street plays out while Cleo, accompanied by Sofia’s mother, is on her way to choose a crib for her baby. She encounters Fermín, now as one of Los Halcones.

In focusing on Cleo and her surrogate family, who are painfully human with all their faults and blemishes, Cuarón makes the film very personal and subjective, therefore becoming universal.

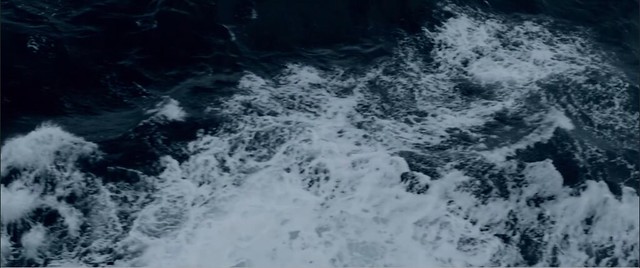

Although the spectacular uncut ending sequence on the beach might be a technical marvel, Cuarón’s craft does not take away from or overshadow the overall emotional impact it has on the audience. The sequence encapsulates everything Cuarón has been working for – pairing technical virtuosity and universal human decency to a maximum impact. Quietly spectacular, this larger format, digitally shot film needs to be seen on the big screen. Hopefully Netflix, its distributor, will release it in theaters for a while before putting it in their streaming queue.

The underlying theme of Roma is giving love and respect to people who we take for granted – those unsung heroes, the backbone of our society. We make movies of spectacles and amplified emotions. Cuarón focuses on miniature crises in one year in the life of Cleo. Roma is a guileless, subtle, deeply felt human story that is definitely Cuarón’s best and most mature work and one of the year’s best films.