In conjunction with the theatrical release of Martel's new film Zama, Film Society of Lincoln Center is hosting the retrospective of one of the most important, daring filmmaker working today. My first encounter was with her much celebrated third feature, Headless Woman/La mujer sin cabeza. It didn't make much impact on me then. I thought the satire on upperclass Argentinian society was, if not cinematically daring, maybe too little on-the-nose. I had no point of reference since I've never seen her previous two films.

It was a German director, Christoph Höchhausler (I am Guilty, The City Below, considered as one of the key members of what critics termed as the Berlin School), who told me that Martel is the filmmaker he admires most when I interviewed him while he was in town three years ago. He pointed at the poster of La ciénaga on the wall of Silversalt PR office in midtown Manhattan, when asked what his favorite film was. Indeed, watching La ciénaga changed everything. Its visual/aural examination of dark and complex underbelly of Argentine bourgeoisie was an eye opener. As an adventurous cinema lover, La ciénaga offered everything I was looking for in cinema. Then Holy Girl, holy moly! I can stress enough the greatness of Martel who is quite possibly the greatest living filmmaker of our time.

I can't find what I wrote about Headless Woman, but here are the my reviews of her other three films for your reading pleasure. Watch Zama on the big screen if you can. It will change what you think of cinema once and for all.

La ciénaga (2001) - Martel

Compared to bombastic, unsubtle satires and social commentaries that we are used to, Lucrecia Martel puts some perspectives on how they should be done, masterfully in La Ciénaga (The Swamp). Taking place in the decaying manor in the jungle in one unbearably hot and sticky Summer in Argentina, the film illustrates the murky underbelly of bourgeoisie without delving into surrealism or making caricatures out of characters. Mecha (Graciela Borges) is seen sunbathing while drunk along with the rest of the inebriated grownups of the house by the pool side. After demanding ice cubes for her wine, she slowly rises in her stupor, tries to collect filthy wine glasses, drops them, falls on top of the shards. The rest of the family are not much better. The emasculated, husband keeps dying his hair and staining the sheets, the 15 year old Momi (Sofia Bertoloto) is obsessed with the pretty native housemaid Isabel (Andrea Lopez), the older daughter Vero (Leonora Balcarce) flirts with her ne're-do-well grown up brother José, who's living with a much older family friend, Mercedes in Buenos Aires, visiting after Mecha's fall and doesn't seem to have problem jumping in mother's bed for a cuddle. Young Joaquin lost one of his eyes while horsing around in the jungle with other boys.

Tali (Mecedes Moran), concerned cousin of Mecha shows up with her family (a grumbling husband, 3 girls and one boy who figure largely into the story later on), not only to check on her cousin but also use the pool for kids who are bored out of their minds. The said pool, neglected and not cleaned for years, is filthy, murky grey disease breeding ground. Isabel warns Momi not to go in there- she might catch something terrible. The contempt for native population is totally out in the open from Mecha down to Joaquin, casually calling them savages and accuse Isabel of constantly stealing towels. With TV always in the background, everyone, across the social strata, is drawn in by the news of appearance of Virgin Mary on top of a cement tower.

With amazing array of characters and richly contrasting social stratification not only in a familial but geographical and cultural, La Ciénaga is a complex examination of a society still steeped in colonial legacy and religion.

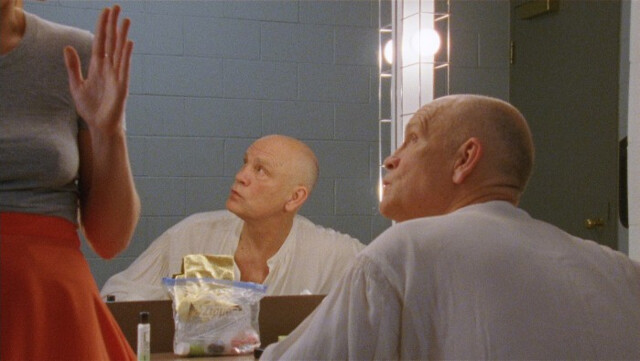

La niña santa/The Holy Girl (2004) - Martel

Amalia (María Alche), a sullen teen girl, lives with her divorced mom Helena (Mercedes Morán) in an old hotel with a thermal pool where mom works as a representative. She attends bible study group with her catholic school girl friends and recite prayers under her breath obsessively. Lately, she is obsessed with 'vocation'. A ear-nose-throat doctors convention is taking place in the hotel. Amalia finds herself being an interest of Dr. Jano (Carlos Belloso), a married man with kids, when he rubs against her bottom in the crowd gathered for a theremin player just outside the hotel. On the verge of sexual awakening with the help of a promiscuous, gossipy best friend Jose(fina), the experience leaves her not repulsed but curious.

She soon becomes obsessed with Jano, sneaking into his shared room, smelling his shaving cream, following him and spying on him at the poolside. Whatever this man means to her, her obsession becomes her 'vocation'. Jano's guilty conscience is not helping Amalia's cause. To make matters worse, Helena finds him attractive as well.

Martel proves to be the master of close-ups and shallow focuses. The details of the senses and small moments she captures on screen - touch, smell, whispers make up the film's superbly orchestrated, organic feel. All the connective tissues of the film are all spread out- the fact doctors are ear-nose-throat specialists - whispers and misheard information, smell, singing, but her approach is so subtle and fluid, you can't help but admire her skills. The Holy Girl is about Amalia as much as it isn't. The film's sordid details of the lives of middle class bourgeoisie can be seen as Almodovar-esque melodrama. But as in all Martel's films there is always a it's-barely-there-but-there satire. I can't really think of any director working today who works on Martel's level. The Holy Girl is a true cinematic feat!

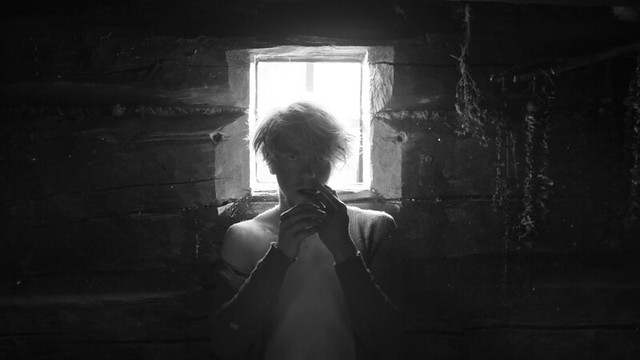

Zama (2017) - Martel

Lucrecia Martel suggested in her introduction to her sold-out screening of the much anticipated follow-up to Headless Woman that we audience might want to take in Zama like a whiskey. Indeed, it's a heady, at times bitter, at times sweet hallucinatory trip to the heart of darkness, showing the white man's identity crisis and misguided manifest destiny in the colonial era Latin America.

The film is a historical period piece, based on the much praised Latin American classic literature by Antonio di Benedeto. It's a hugely ambitious undertaking for Martel with just 3 films under her belt. But if anything, Zama confirms Martel one of the greatest directors of our time. Her mastery over the medium both in complex narrative storytelling and technical ingenuity has grown to exceptional height with Zama.

Don Diego de Zama (Mexican actor Daniel Giménez Cacho with an impressive Romanesque nose), a magistrate stuck in some unnamed South American colonial town deep inland in the 18th century, is anxiously awaiting to hear from the Crown (of Spain), his new assignment to the city. Even though he is a man of certain position and been stationed there for a while, he can't ever seem to get ahead or get what he wants - the letter of transfer never materializes, his rival Ventura (Juan Minujín) is much better at kissing asses and the local society lady de Luenga (Lola Dueñas) flirts with him but wouldn't give in.

Zama doesn't fair well with the natives either- seen in the beginning peeping at nude women taking mud bath and getting caught. He also has a nagging native woman he had an invalid child with. And the thought of the existence of this child weighs in his conscience like a brick. His misplaced valor to protect three virginal sisters is always overshadowed by the overhanging threat of a mythical bandit named Vicuña Porto who is notorious for raping and pillaging.

After physically threatening Ventura over de Luenga, Zama is demoted and moved out of his semi-opulent living quarters to a squalor with rotting walls, just outskirts of a city. At the governor's insistence and a promise of recommendation letter to the Crown, he delivers a scathing review of a book written by a well-meaning, trusting young civil servant (the governor can't stand the thought of the young man wrote the book while on the job). But no matter how many favors, how many people he fucks over, Zama realizes that he won't be leaving the backwater town any time soon.

Fallen out of favor and aging, Zama reinvents himself as a guide to the band of soldiers in the late stages of colonization. As they advance inland, they are terrorized by the red body paint natives who populate the land. Fighting with the elements and among themselves (one of the soldiers claims to be the elusive Vicuña- is he really? Does it even matter?), Zama and the men get completely lost in the strange land.

There have been countless other films about the white men's delusion of grandeur- Aguirre, Wrath of God and Apocalypse Now! easily come to mind. With Zama, along with lyrical Jauja few years back, directed by fellow Argentine Lisandro Alonso, Martel captures the existentialist angst in the age of colonialism/ad infinitum in Latin America with astonishing efficiency and grace. Shooting digital for the first time, Martel and her Portuguese DP Rui Poças (Tabu, The Ornithologist, To Die Like a Man), create lush, bright palates that are intoxicating and hallucinatory.

Martel's mastery of the cinema medium as sensory medium first and foremost is nothing short of brilliant. She subjects us to painterly framing and exceptional sound design in every scene. Those of you who followed her trajectory closely through La Cienaga, Holy Girl and Headless Woman and have been admiring her artistry will be richly rewarded here - a carefully measured framing where people's faces are just off the frame, shallow depth of field, soft focus, the full use of background/foreground and the use of dialog fading in and out with internal monologue thrown in, just to name a few.

She also uses the Shepard Tone whenever there is a dramatic moment for Zama. The tone is an illusory aural phenomenon that creates continuously swelling sound which builds tension and suspense. All these are very simple methods and not radical experiments at all, but it's Martel's simple approach that makes everything so fresh and radical. As you watch Zama, you can't help but feeling that you are watching a true cinematic masterpiece.

Finding the Latin American identity, as European settlers and their offspring, has been the continuous source for great literature over 300 years. Throw in the idea of class, masculinity, racism, sense of belonging, you get a very complex picture of what makes up the theme of Zama.

As usual, in Martel's hands, what seems to be an extremely messy affair at first, the sense of cohesiveness emerges from the chaos, then the sense of warm comfort wraps around the whole experience. Even though Zama is a lost character who goes through traumatic experiences, there is sense of catharsis that is reached in the last moments of the film. That he finally found home, that he reached his el dorado, imagined or otherwise. Zama is a utterly brilliant film. See it on the big screen if you can.